Gary Hevel finds a backyard bonanza of bugs

A longhorn beetle munching milkweed just over a fence in the neighbor's yard was a covetous sight for Gary Hevel, public affairs officer in the Entomology Section of Natural History's Department of Systematic Biology. No longhorns crawled on the milkweed in his own yard, and this species of longhorn beetle would make an excellent addition to his insect survey.

Ultimately, Hevel's scientific integrity prevailed. He left the beetle where it was. "I'm very strict about that," Hevel states. "I only collect in my own yard."

Since July 2000, Hevel has collected some 2,200 different species of insects in his two-acre yard in Silver Spring, Md. From bark lice and pantry moths to sawflies, cicadas, mantids, grasshoppers, ladybugs, weevils, lacewings, mosquitoes, stoneflies, katydids, butterflies and moths, bees, aphids and beetles, Hevel is making an all-out effort to leave no insect species undetected and unrecorded.

|

|

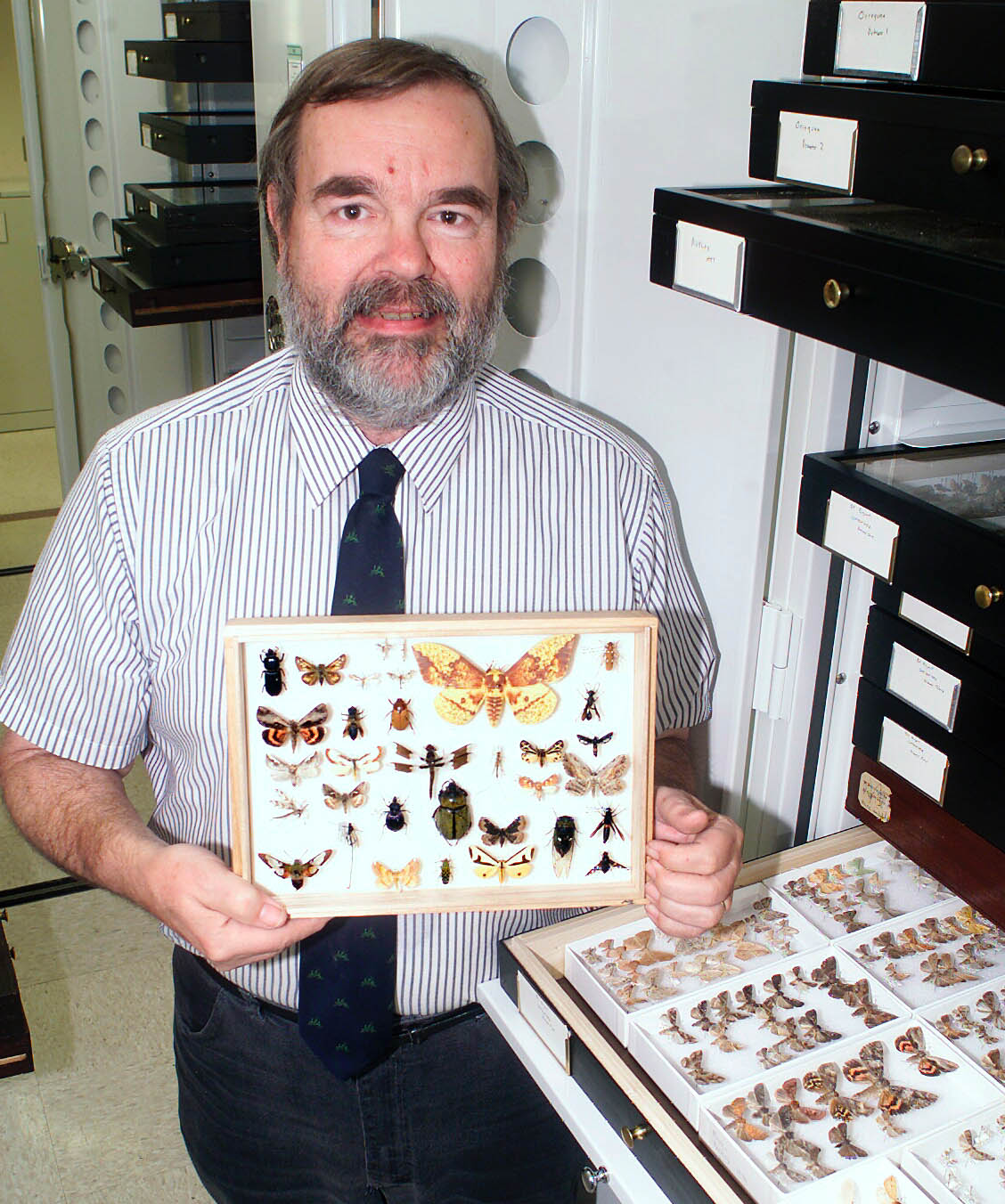

| Gary Hevel shows off some of the more than 2,200 insect species that he has collected in his yard in Silver Spring, MD. Copyright 2002, Smithsonian Institution. |

His project, which is to take place during a two-year period, vividly illustrates what few people realize that a remarkable world of thousands of insect species thrives virtually undetected beneath our noses. It also demonstrates that the staff and collections of MNH'sEntomology Section are an unmatched resource for insect identification and knowledge.

While Hevel may not pluck a beetle from a neighbor's milkweed, he's not above luring insects onto his property with such temptations as rotten fruit, dead mice and black lights that beckon to bugs passing in the night.

About 70 percent of the insects I catch come from my traps, Hevel explains. The other 30 percent come from Hevel's crawling through grass, peeling the bark off of dead trees, flipping over rocks, wandering through his garden, perusing the woodpile and making certain to visit specific trees, particularly when they are in flower. Hevel frequently uses a ladder and a long-handled net for collecting insects living high in trees.

Then, there's always a beetle or other insect that comes stumbling through the clothes-dryer hole in my basement wall as I'm collecting the laundry, he adds.

The project is a personal one for Hevel, who says he was inspired by a 1941 book by Frank Lutz, titled A Lot of Insects. In it, Lutz humorously describes his collecting of some 1,402 insect species in his own yard in New York over a four-year period.

Hevel does most of his collecting on weekends and evenings, he says. In the beginning, I ambitiously thought I could complete the project in one year, Hevel recalls. ABut I learned that one person just cannot keep up with it very well.

After the insects are collected, the hard work follows sorting out the new species and then identifying their family and species. For this part of the project, Hevel relies on his own knowledge and the expertise of National Museum of Natural History (MNH) entomologists and the museum=s insect collection of some 30 million specimens.

Smithsonian and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) taxonomists here are pretty much worth their weight in gold, Hevel observes. AEvery day, they receive insect specimens in overnight packages from USDA inspectors at airports, ocean ports and border crossings nationwide. The swift identification of these insects taken from agricultural products being imported into the United States is mostly the work of USDA entomology staff and has prevented any number of foreign insect pests from invading this country.

To identify a tiny sawfly that turned up in his black-light trap, Hevel looked to the MNH collections. Sawflies are, in fact, wasps, of the order Hymenoptera, which is Greek for Amarried wings, Hevel says. In the collections, Hevel was confronted with many cabinets filled with thousands of sawfly specimens.

Matching his sawfly to the correct species in the collection may have taken weeks, if he could have done it properly. With the assistance of USDA Entomologist David Smith, an expert in sawflies and primitive wasps, the species of Hevel's specimen was quickly identified Macrophya cassandra. Other MNH experts in moths, caddisflies and mosquitoes have also come to Hevel's aid.

A lot of insects I recognize, but a lot I certainly don't know, such as the microlepidoptera (tiny moths) and microhymenoptera (tiny wasps), he says. AMNH is one of the best places in the world for this kind of research, Hevel adds.

There are so many insects in the collections here, and often, they are known by only one specimen. We also keep a wealth of manuals, guides and background information on each species that has been amassed over time, such as what plant it was feeding on when it was collected, the general time of year the insect emerges, variation within species, as well as between species, and the different patterns within a species.

Hevel labels each insect with its species name, the location Maryland Mg. Co., 4 mi. S.W. of Ashton and the longitude and latitude of his yard and the date the specimen was collected. He then mounts each on a pin in a glass-and-wood case.

Hevel will continue collecting until July 2002 and then compile a list of all the insect species he has collected. The winter weather has given him a respite from collecting, but not entirely.

There are at least two species that appear in winter, he notes. One is a small stonefly that shows up on storm windows and doors. The other is a cankerworm moth, an odd thing,the male is fully winged and gray in color. The female is wingless, just a ball of fuzz walking around.

February 2002

Prepared by the Entomology Section, Dept. of Systematic Biology

National Museum of Natural History, in cooperation with Public Inquiry Services