Hirshhorn visitors fill Yoko Ono’s “My Mommy is Beautiful” with intimacy and intensity

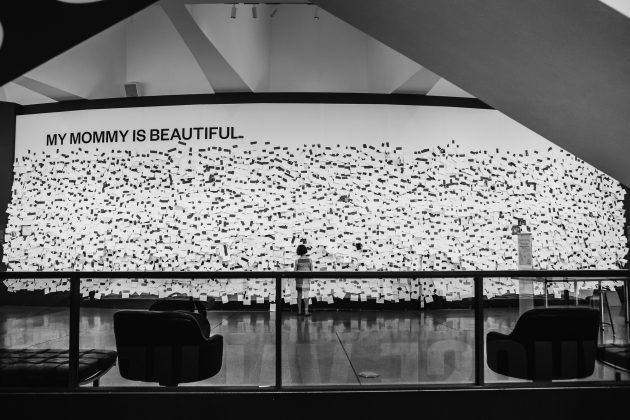

A girl contemplates the postings to Yoko Ono’s “My Mommy is Beautiful,” in the lobby of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Emily Karcher Schmitt)

It’s morning in the lobby of the Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and a little girl with bobbed hair, maybe 6 or 7 years old, stands over a long table, pencil in hand. Nearby, her mother reaches for a large dispenser of brown tape as she holds a photograph of a little boy smiling with a gray-haired woman.

Together, this mom and daughter choose a spot on the wall—a living shrine, of sorts, to matriarchy called “My Mommy is Beautiful”—a conceptual art installation by Yoko Ono on display for a limited time in Washington, D.C.

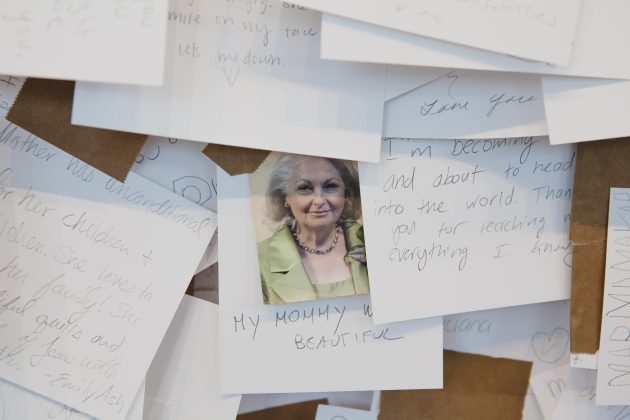

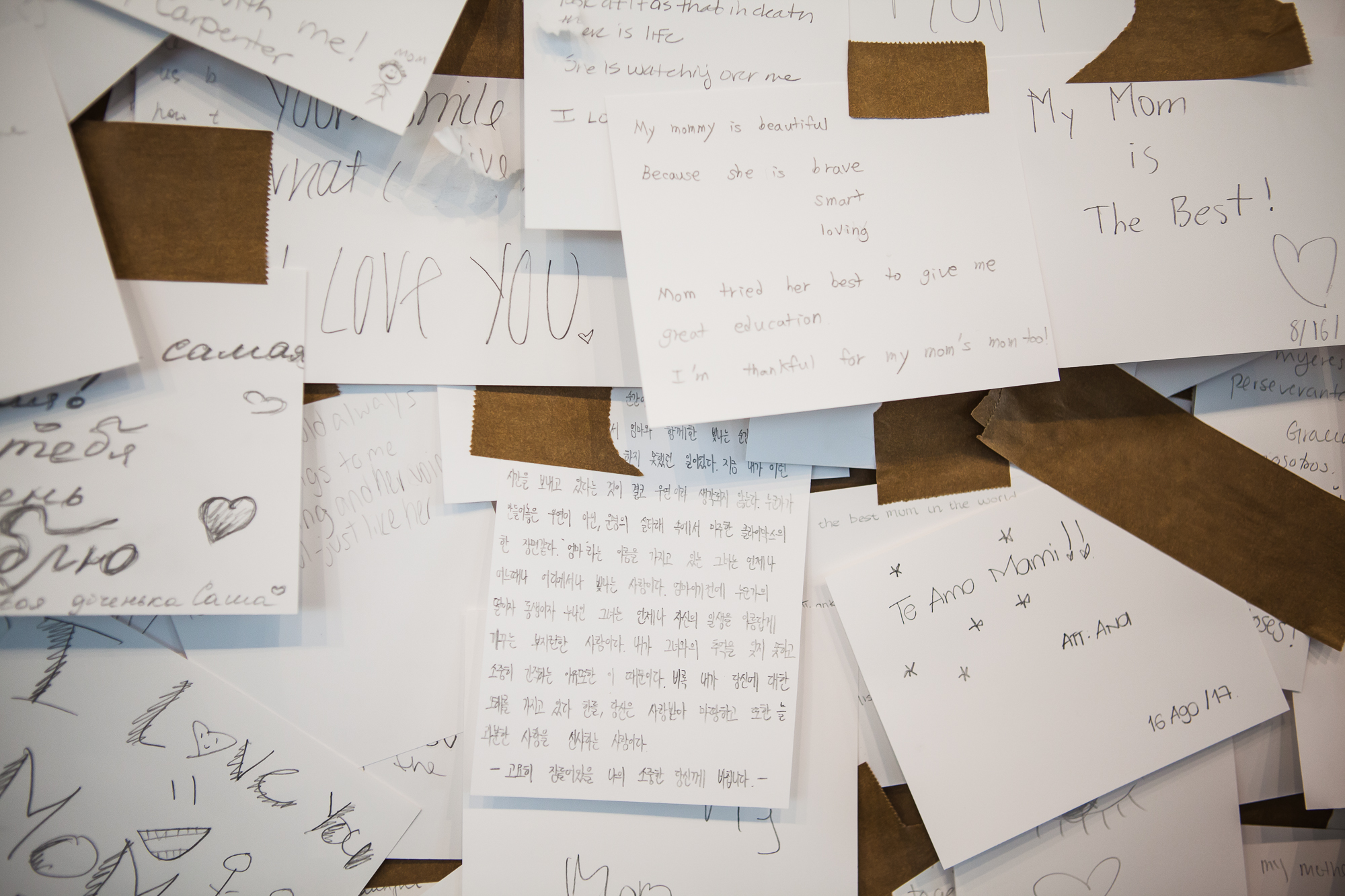

An invitation in Ono’s handwriting invites visitors to “Write your memory of your mother and/or paste a photograph of her on the canvas.” Those who participate experience the power of the piece. At a distance, the little strips of paper and tape on the “My Mommy is Beautiful” wall could be sprinkles on a cake or an Impressionist snowfall. But up close, the complicated intensity of motherhood and the child’s reaction, one by one, slips out–each revealing one tiny piece of an intricate puzzle.

Many messages are written in foreign languages, some foreign alphabets. Some include photographs, some pencil illustrations of their mother’s features: smiling eyes, a long neck, flowing hair, and written notes like: “Mommy, you are everything to me, to us, and you always will be. You were my first love, you are my best ‘buddy’ always,” signed “Geetz.” Or, “I have two mothers, one I never met and one who chose me. Thank you for letting me go, thank you for choosing me. Today I am 21 and I love you.” Simpler ones say things like, “My badass mom beat cancer!” or “She wrote the children’s health insurance policy legislation.”

After only two months on display at the Hirshhorn, where the piece opened June 17, visitors already have taped up more than 20,000 messages and memories of their mothers.

“I thought by the end of the three-month run, we might have filled the wall, but the wall was full in two weeks,” says Mark Beasley, curator of media and performance at the Hirshhorn. “So you never know. But you trust an artist, and Yoko always knew.”

The wall itself now protrudes—particularly in the popular middle—because of the sheer numbers of papers stuck to each other, bulging outward. Versions of “My Mommy is Beautiful” have been in various venues since 2004, and the installation also has a dedicated online and social media presence. When the current iteration is removed, Ono has requested each note and photograph be sent to her.

Beasley’s position is a new one for the museum, started as part of Hirshhorn Director Melissa Chiu’s emphasis on cultivating interactive experiences for visitors. Serving under the leadership of Chiu and Chief Curator Stéphane Aquin, Beasley organizes exhibitions and works to enhance the museum’s collection of new media art, which includes film, video and performance.

Beasley describes the exhibit as a “coral reef of living thoughts and ideas about people and family,” and sees it as a key work in building the museum’s offerings.

“The install in the lobby is to present works that are active and participatory, which is a newer thing for the museum. It is something museums are picking up all over,” Beasley adds.

“My Mommy is Beautiful” offers visitors an opportunity to bridge the gap between the soul-bearing chatter of social media and the more traditional process of putting a pencil to paper. Middle-school boys to grandmothers have participated, often posing for selfies with their notes behind them on the wall.

“I think people are looking for moments in real time that aren’t mediated, that isn’t accessed through a screen,” Beasley says. “People post all kinds of thoughts on Instagram, but it feels very different when you’re in a space, and you’re writing and there are people around you and you’re committing to this. It feels very different. I think the moment of the encounter when you’re thinking of what to write is real engagement.”

Ono is known for conceptual art that provides visitors with artistic tools so they can be part of the creation of an artwork itself.

“I believe thinking is a creative act, and this work—for me—is answering the key things that I think of when I think of what art is: It’s something that both challenges and allows you space to think,” Beasley says.

“My Mommy is Beautiful” creates a venue for visitors’ honest reactions to their mothers. Ono had a complicated relationship with her own mother.

“It’s amazing what people will write and leave on a wall,” Beasley observes. “It’s very raw, and it’s not all ‘I love Mom.’”

Beasley feels it is important for the Hirshhorn to be a space where many ideas can meet, unbiased and unfiltered, and people can come to their own conclusions.

“It is key to have a space that’s open to many ideas that are allowed without judgment,” Beasley says. “We’re preloaded with judgment. We teach our kids whether we want to or not. We teach rules and then hope that the individual is given enough insight to make sense of things for themselves, and I hope that’s what the museum does.”

“My Mommy is Beautiful” is part of a group of presentation-based works this summer collectively titled “Yoko Ono: Four Works for Washington and the World,” which will culminate in a one-night-only performance of Yoko Ono’s music called “Promise Piece,” on Sept. 17, the day “My Mommy is Beautiful” will close. The other works include Ono’s “Wish Tree for Washington, D.C.,” which was acquired a decade ago and continues to engage visitors in the Hirshhorn’s Sculpture Garden, as well as Ono’s “Sky TV for Washington, DC” (1966) on display on the museum’s third level.