Women “computers” mapped the universe in the 19th century

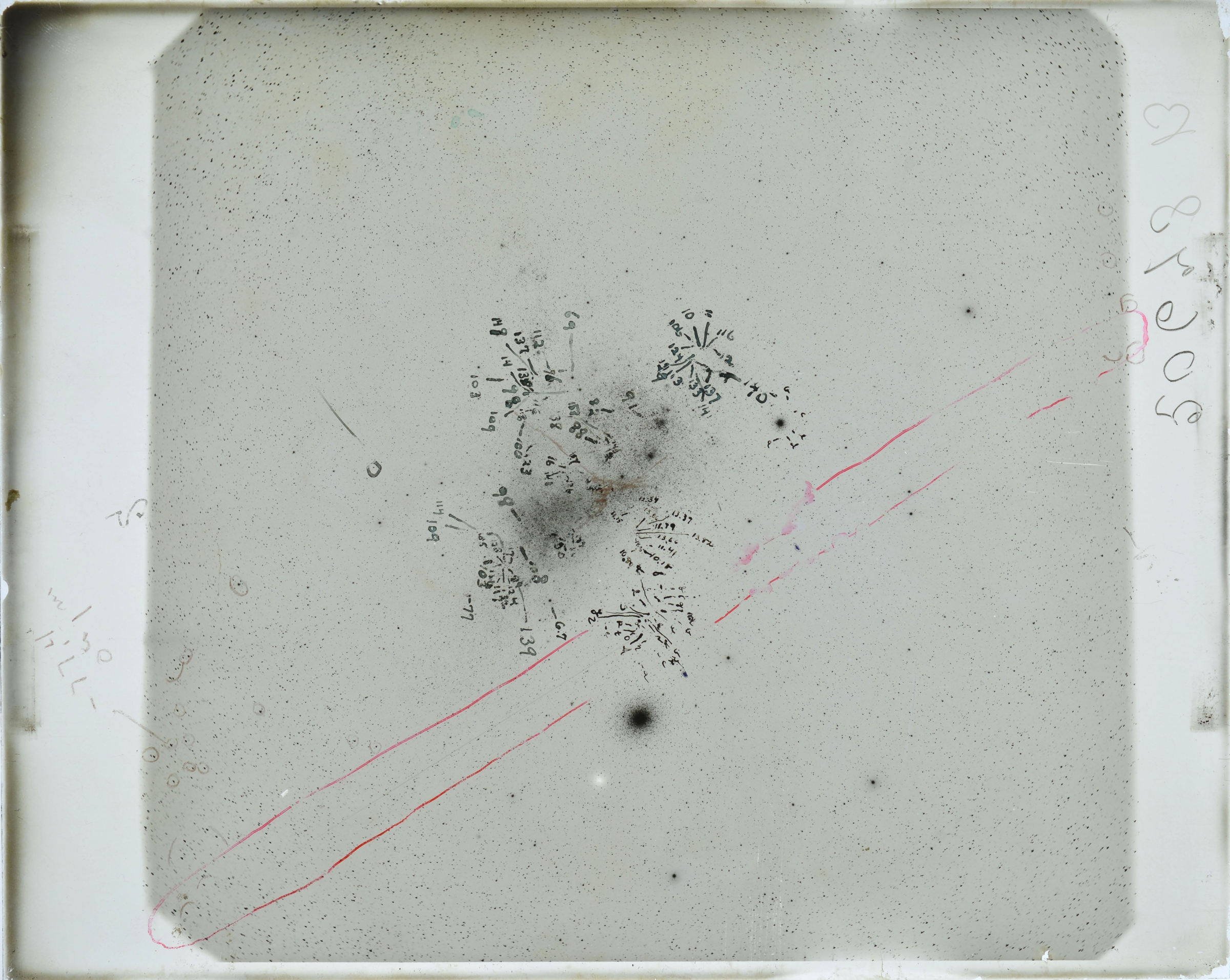

Williamina Fleming (standing) supervises the team of women “computers” at the Harvard College Observatory as they help map the universe – one star at a time. (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, Glass Plate Collection)

Every day, astronomers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics depend on computers to help them solve the mysteries of the universe, just as they did in the late 1800s. But at that time the term “computer” didn’t refer to a hard drive, keyboard and monitor—it was the title given to the pioneering women who used glass-plate photography to chart and study stars and other celestial objects.

In 1875, the center in Cambridge, Massachusetts—then known as the Harvard College Observatory—began hiring women computers.

One of the first was Anna Winlock, whose father worked at the observatory before his death in 1875.

With an aptitude for mathematical astronomy, Winlock approached the center for a job in calculations. At a much lower wage than her male counterparts (25 cents an hour), she and three other women “computers” were able to quickly analyze and reduce a huge backlog of scientific observations that had been jotted down by the male astronomers, who worked overnight with telescopes.

The women computers began studying and caring for the observatory’s growing glass plate photograph collection in 1885. In analyzing the images of space, the women’s duties included measuring the brightness, position and color of stars, classifying stars by comparing the photographs to known catalogs, discovering new stars and counting galaxies.

As a result of their work, the observatory published the first “Henry Draper Catalog” (named for the trailblazing astro-photographer) in 1890. The catalog contained more than 10,000 stars classified according to the spectrum of electromagnetic radiation radiating from each star. Draper’s widow, Anna, generously donated funds to help expand the women computer program.

“What amazes me most about the women computers is that they studied the stars at the Harvard Observatory during a time when very few women had careers in the sciences,” says Lindsay Smith Zrull, curator at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. “It’s hard to imagine today, but women’s higher education was still hotly contested in this era—women didn’t even have the right to vote! And yet there they were making profound discoveries about the organization of the universe.”

On more than one occasion, the women computers improved and redesigned the classification system for stars. They ultimately developed the Harvard Classification Scheme, which is the basis of the system used today.

The brilliant insight of computer Henrietta Swan Leavitt led to our modern understanding of the universe’s true size.

Leavitt started at the Observatory in 1895 as an unpaid assistant. Using glass plate photographs, she studied stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud (a dwarf galaxy near the Milky Way) whose brightness varied.

She reasoned they were all roughly the same distance from Earth and found a pattern in the length of their brightness. Her method— Leavitt’s Law—is used to determine astronomical distances.

At a time in America when women’s job opportunities outside the home were largely confined to a classroom or factory, the women computers at the Harvard College Observatory were challenging the norm. Many advanced to respected careers as professional astronomers: Williamina Fleming discovered the Horsehead Nebula in 1888, and Annie Jump Cannon is credited with creating the Harvard Classification Scheme.

From the few women who started as underpaid “computers” in the 1880s, the role of women in astronomy and astrophysics has grown enormously. Today about 100 women scientists work at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, exploring the reaches of the universe.