Jamestown skeletons identified as colony leaders

A team of scientists used multiple lines of evidence, including archaeology, skeletal analyses, chemical testing, 3-D technology and genealogical research, to single out the names of the four men who died at Jamestown from 1608 through 1617. (Photo by Donald E. Hurlbert)

Within the 1608 church where Pocahontas and John Rolfe married, the skeletal remains of four early settlers were uncovered during a 2013 archaeological dig at Virginia’s historic Jamestown colony. Now, those bones have been identified as some of the leaders of that first successful British attempt to forge a new life in the new world across the Atlantic.

Forensic anthropologist Douglas Owsley, the division head of physical anthropology at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, and his team worked with archaeologists from the Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation at Historic Jamestowne to piece together just who the four men were.

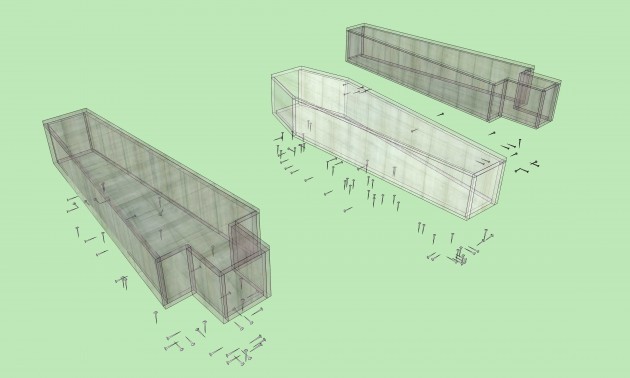

Built first of mud and wood, the original church structure had long since vanished. Archaeologists rediscovered the church’s original footprint five years ago.

Only about 30 percent of each skeleton was recovered, and the bones were poorly preserved, so finding out who the men were presented a challenge that required multiple paths of investigation.

The first clue to their identities came from the burial location in the chancel, a space at the front of the church around the altar reserved for the clergy. Only leading members of the community would have been buried there, so it was clear the men had a place of prominence among the colonists.

The research team then came up with a small list of prominent men who died between 1608 and 1617 and narrowed the list of potential candidates using the few surviving historical records. They tested the skeletons to determine their sex and approximate ages at death, sifted through detailed genealogies, examined diet through chemical testing and used high-resolution micro-CT scanning to reveal facts about the artifacts that were buried with the men.

Eventually, the team identified the men as:

- Rev. Robert Hunt, the chaplain at Jamestown and the colony’s Anglican minister, who died at age 39 in 1608

- Capt. Gabriel Archer, who died at age 34 in 1609 or 1610 during the “starving time”

- Sir Ferdinando Wainman, who came to Jamestown with his first cousin, the governor of Virginia, and died at about age 34 in 1610

- Capt. William West, who died in 1610 during a skirmish with the Powhatan at age 24

The men lived and died at a turning point in the history of the settlement—when it was on the brink of failure due to famine, disease and conflict. “The skeletons of these men help fill in the stories of their lives and contribute to existing knowledge about the early years at Jamestown,” Owsley says.

This discovery also comes at a critical time in Jamestown’s present history, as preservation of these materials is threatened by ongoing changes in the soil and water levels at the site. Jamestown is susceptible to sea-level rise, which some scientists predict could submerge the island by the end of the century.

Owsley’s career has been marked by many stories that anthropological discovery has brought to the world, including the examination of Kennewick Man, one of the oldest skeletons found in America, and evidence of cannibalism in Jamestown. Asked to describe the best part of his job, he says, “When it all becomes clear—the spectacular moments where you understand what’s going on.”

Owsley’s team, including physical anthropologist Kari Bruwelheide, Data Management Specialist Kathryn Barca and Scanning Electron Microscope Laboratory Manager Scott Whittaker, will continue to further document and conduct historical, archaeological and genetic research on the skeletons to better understand what life was like in the early 17th-century Chesapeake area.

The Smithsonian’s 3D Digitization Program Office scanned the excavation and archived the data so people anywhere can download and interact with the burial sites. Through their bones, these men’s stories live on.