From past to present: How the Smithsonian pioneered weather forecasting and climate research

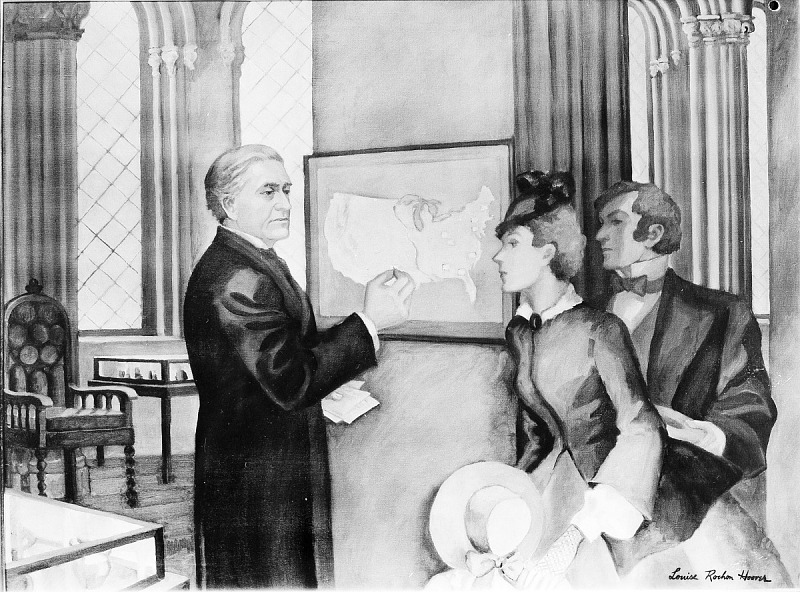

This painting by Louise Hoover depicts Joseph Henry (on the left) showing a daily weather map displayed in the Smithsonian Castle. Image: Louise Rochon Hoover, 1933. Smithsonian Archives - History Div, 84-2074 and 31052-E and 94-12563.

The Smithsonian invented the modern weather forecast at the time of its founding and has continued collecting data on climate and weather ever since. For nearly 180 years, researchers at the Smithsonian have asked questions about the global climate and its variable weather patterns to determine their impact. Here are four important examples of how the Smithsonian has contributed to weather and climate research throughout its history.

The First U.S. Weather Forecasts

Anyone with a smartphone can receive up-to-the-minute weather forecasts with a couple taps on a screen. Temperature, cloudiness, precipitation, air quality—it is all available in an instant. But in 1846 when the Smithsonian was founded there was no reliable way to predict the weather, and the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Joseph Henry wanted to change that.

Having studied meteorology in college, Henry wanted to use his new platform—the Smithsonian Institution—to gain a better understanding of the weather. He established the Smithsonian Meteorological Project, where he organized a group of 150 volunteers and dispersed them around the U.S. to collect weather data. Volunteers sent back monthly reports via a novel technology called the telegraph, which Henry had predicted would be useful for this exact purpose.

With mounds of data collected, a dozen people were dispatched to analyze it all. From the data, Henry discovered that some weather systems travel from west to east (thanks to what later would be identified as the jet stream), while others move from the Southern U.S. to New England (these are now called Nor’easters).

This work was the first systematic study of weather patterns in North America and led directly to the creation of the National Weather Service.

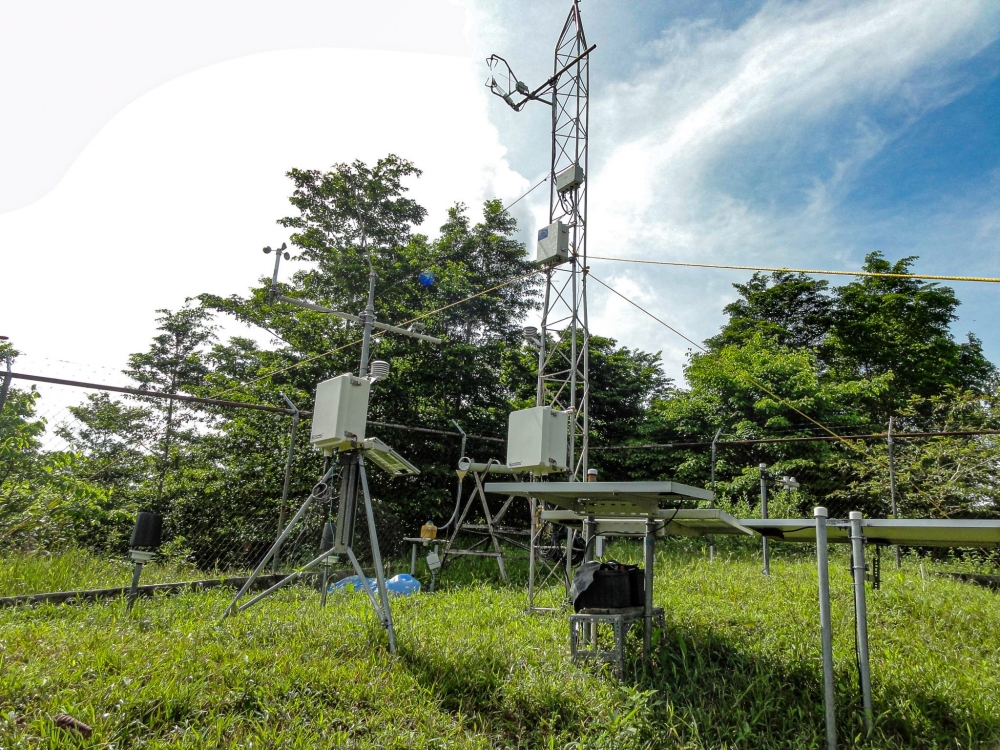

Understanding the Seasonality of the Tropics

Over 100 years later, in 1972, the Smithsonian embarked on another large-scale environmental monitoring program. Stations built at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama and at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) in Edgewater, Maryland, still take measurements today that help researchers learn more about weather and local climate.

Steve Paton has been running the Physical Monitoring Program, now part of the Agua Salud project, for more than three decades on Barro Colorado Island, STRI’s primary research station in Panama. The data his team has collected has been used in hundreds, if not thousands of scientific publications. Among the program’s greatest contributions to climate science, STRI’s data enabled scientists to define the wet and dry seasons in the tropics. More recently, the information allowed us to better understand and contextualize drought conditions in Panama and their impact on the Panama Canal.

The Future of Our Coastal Ecosystems

Coastal ecosystems form a buffer between the ocean and the land. Marshes, for example, help protect our coasts from flooding and erosion. They also help keep coastal water clean, host plants that feed marine animals, and store carbon. Coastal forests also store carbon and provide shelter and food for animals. It is difficult to predict exactly how these ecosystems will be impacted by climate change.

Instead of merely predicting future climate change, SERC scientists are mimicking what the world’s climate may look and feel like 100 years from now. In coastal forests on SERC’s campus, they are flooding the grounds with freshwater to simulate increased precipitation and salt water, the predicted result of sea level rise. On their 70-hectare marsh, they are using chambers to increase carbon dioxide and nutrient pollution, and they are heating up sections in different combinations. The scientists have found that, to a point, climate change helps plants grow before it hurts them, indicating we might still have time to prevent the worst effects of climate change.

Monitoring Air Pollution in Near-Real-Time

The growing presence of wildfire smoke in many Americans’ daily lives reminds us that rain, wind, and extreme temperature are no longer the only weather conditions that affect our lives. Many of us, especially those with asthma and heart disease, must also consider the cleanliness of the air we breathe. Fortunately, air quality measurements are becoming more accurate and useful thanks to a collaboration between the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and NASA.

They collaborated to launch the Tropospheric Emissions: Monitoring of Pollution (TEMPO) probe into orbit in April 2023 to track air pollution across North America in near-real time. Unlike today’s ground-based monitors and satellites, which only collect air data in specific regions, the TEMPO probe scans almost the entire continent once per hour at neighborhood-level resolution. The first visual results beamed down in May 2024. The data is now available to third-party app developers, which means hourly, zip code–specific data will be at the tip of your fingers soon.