Logan Kistler hopes to solve modern problems by studying ancient DNA

“That’s Miss Tilly," Logan Kistler says. "She’s about half Arctic dog ancestry (malamute, husky, etc.) and the other half most resembles a mishmash of German shepherd, golden retriever, this and that.” Image: courtesy Logan Kistler

Unfortunately, we cannot recreate Jurassic Park in real life, according to Dr. Logan Kistler, an expert in ancient DNA at the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH). One of the many, many things mitigating our ability to run with raptors and swim with Megalodons is that it is simply not possible to recreate actual dinosaurs. “Dinosaurs are so old that there probably isn’t any dinosaur DNA left on Earth,” Logan told Eye on Science. “Sure, if you were able to store DNA on the dark side of the moon, it could remain stable for millions of years. But on Earth, it cannot survive for long, even in permafrost. Over time, it thaws and freezes too many times.”

We’re sorry to extinguish any lingering hopes that the Smithsonian might one day include dinosaurs among the species in the care of the National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute. But our story is much more interesting than anything mere movie magic can conjure. Logan, the curator of archaeobotany and archaeogenomics at NMNH, has spent his career pursuing the origins of human society itself, as told through ancient genetic material. Logan told Eye on Science that it is empowering as a scientist to focus on pure research—without being concerned about its direct application—that answers fundamental questions about who we are. At the Smithsonian, he has the freedom and opportunity to ask big questions that will take time to resolve, but will pay off by informing solutions to society’s most complicated challenges.

Since there isn’t any dino DNA around these days to study (not even preserved in amber), these bird-lizards are never even mentioned in Logan’s lab notebook. Instead, he collaborates with other scholars to study the DNA of animals and plants that died relatively more recently, whose DNA still exists in bits and pieces in caves, rock shelters, and deserts. His first love is paleobotany, the study of prehistoric plants, but as the ancient DNA guy at the Smithsonian, his research covers many different queries. “I am always going to revert to plants when I can, but because I work with so many research fellows, my work ends up touching many areas,” Logan said. And that includes everything from small mammals to agave to extinct breeds of dogs.

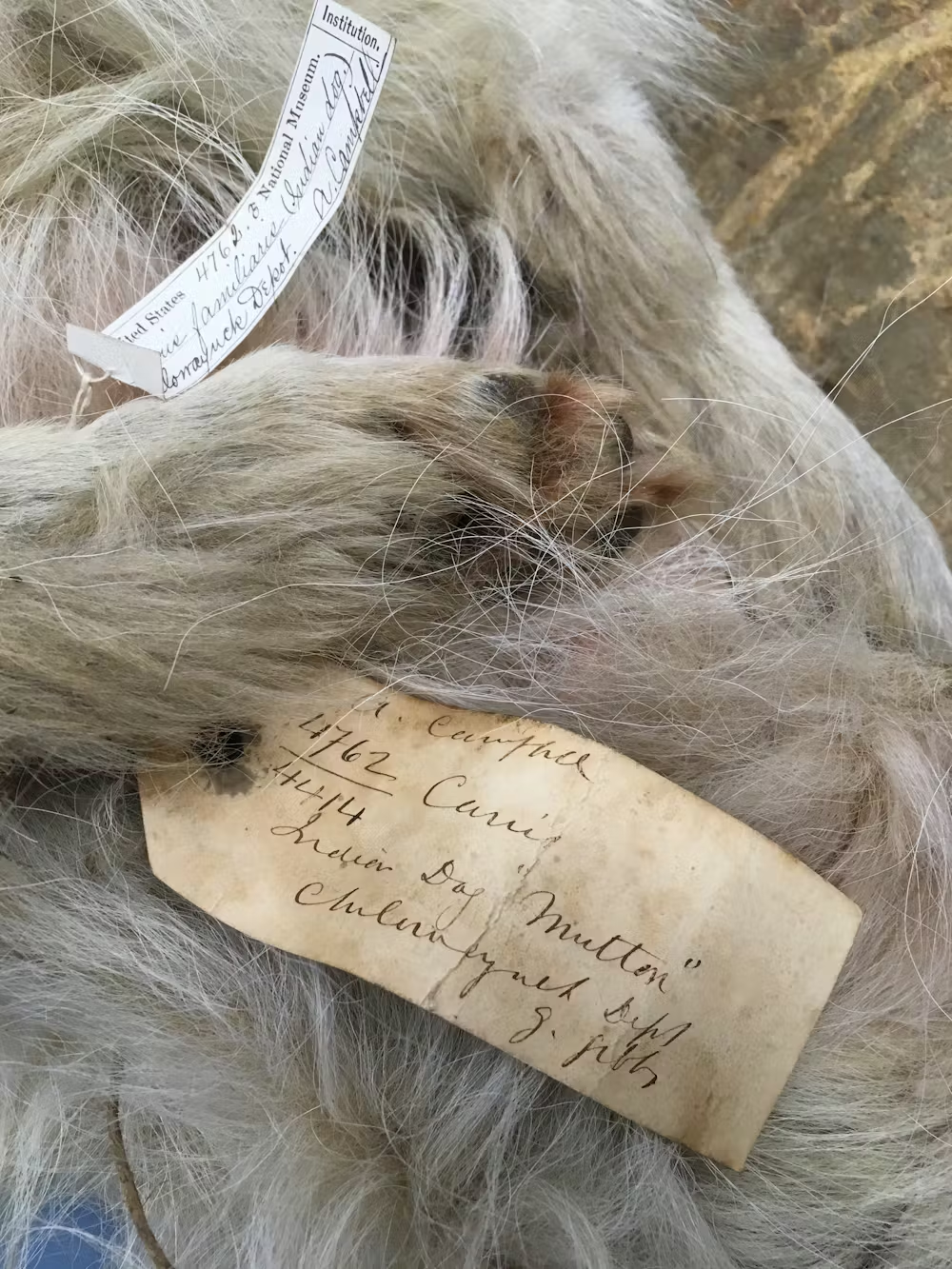

In fact, one of Logan’s most popular studies in 2023 was about an extinct Indigenous breed of woolly dog. Working with post-doctoral scholar Audrey Lin, scientists from the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute and others, Logan studied the genetic and cultural heritage of this animal to reveal how it came to be and why it went extinct. The paper received wide media coverage (because who doesn’t love stories about dogs?) and Logan co-wrote an article about the research for The Conversation, which helped the team garner media coverage in several dozen smaller media outlets around the world. As a testament to Logan’s eagerness to answer questions about his work, he revisited the article to answer questions from readers.

Even though the paper was a success, not everyone was happy with Logan’s research on the woolly dog. “My dog Tilly was sad when I was working on it,” Logan told us. “I couldn’t have her hair on me for fear of cross-contamination, so I couldn’t get near her.” The research involved studying the last remaining woolly dog pelt, which is housed within the Smithsonian’s natural history collection. “Tilly’s a COVID adoptee, and she’s the one making the sacrifices,” Logan said. “Doing lab work means we have to think in unexpected ways sometimes.”

Although Logan relishes studying any ancient DNA, including dogs (which are pretty darn cute, even the extinct ones), his happy place is working in the lab with a pile of weeds.

Years in the field have taught him why plants are so important. “Plants have been coevolving with humans for thousands of years,” he told Eye on Science. “We humans, as a species, are utterly reliant on plants. Maize, wheat, and rice give us half of our calories every day.” Not only does consuming plants keep us alive and healthy, but also “understanding how the relationship between humans and plants has developed helps us understand what’s needed to produce food sustainably, adapt to climate change, and protect the environment,” Logan said.

Logan is especially interested in genetic diversity within plant species, because without diversity, we get into big trouble sometimes. “The Cavendish banana [the common yellow banana found in every supermarket] comprises 99 percent of bananas exported in the world. But this species is now threatened by a fungus in southeast Asia. The Great Famine in Europe is another example. The continent’s potato crop lacked biodiversity, and that led to massive collapses [when the potato crop failed due to disease],” he said. “Ancient plants tell us how we got here and how our actions going forward are going to shape the next 1,000 years of food production.”

Logan cherishes his role at the Smithsonian not just because he can study big themes such as plant diversity, but also because it grants him a lot of opportunities to interact with the public. “I’ve done a lot of public events; I’ve met with school groups,” he said. And the questions keep coming. One that appeared in the comments section of The Conversation article makes the logical leap from wooly dogs to wooly mammoths, asking, “Can we really bring back the woolly mammoth?”

Although efforts are underway to clone a wooly mammoth, Logan insists that, sadly (or not, depending on your feelings about enormous hairy quadrupeds with 8-foot-long spears for teeth), the mammoth is not coming back since its ancient DNA is too degraded to clone. There are also too many technical barriers to overcome. For example, where would you find a spare woolly mammoth uterus to nurture a cloned embryo for what we assume would be about a two-year gestation? Instead, Logan says scientists could possibly edit the genome of elephants to give it mammoth-like features. “We might have hairy elephants walking around one day,” he said.

Which raises the very real ethical question explored by the fictional Jurassic Park films: We may be able to do it, but should we?