Finding and Describing the World’s Creepy-Crawlies

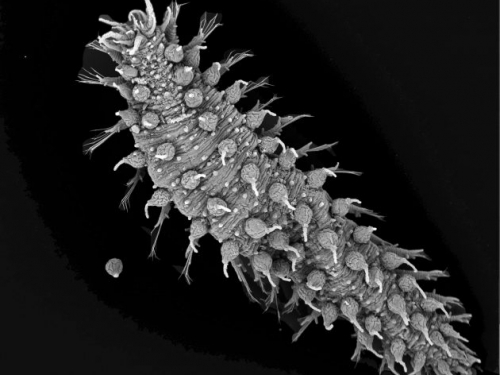

These three specimens of M. sestertia in the collections of the National Museum of Natural History (dorsal, top, and ventral views shown here) were collected in 1936.

Bugs and worms comprise nearly a quarter of the Smithsonian’s entire collection. Totaling roughly 35 million specimens, the Smithsonian’s entomology, or bug, collection is one of the largest in the world. Combined with the worms in the invertebrate collection, they serve as a reference library for researchers, a source for exhibitions and educational materials, and as a place of inspiration for all who are interested in the natural world.

The world’s knowledge of bugs and worms keeps growing, thanks to teams of scientists, collaborators, and volunteers from around the globe who share a goal of cataloging the world’s biodiversity. Here are four examples of bug discoveries from the Smithsonian:

New Medicinal Leech in the Smithsonian’s Back Yard

In 2019, we saw the discovery of the first new species of North American medicinal leech in 40 years, thanks to researchers at the National Museum of Natural History. The “medicinal” quality of this leech does not mean it will be used in hospitals; rather, the term means the leech can readily feed on human blood.

The new species, named Macrobdella mimicus, was first identified from specimens collected in southern Maryland. This prompted a search through marshes and museum collections that ultimately revealed the leech has long occupied a range that stretches throughout the Piedmont region of the Eastern United States, between the Appalachian Mountains and the Atlantic Coast. “We found a new species of medicinal leech less than 50 miles from the National Museum of Natural History—one of the world’s largest libraries of biodiversity,” Anna Phillips, the museum’s curator of parasitic worms said at the time. “A discovery like this makes clear just how much diversity is out there remaining to be discovered and documented, even right under scientists’ noses.”

You can take a virtual tour of the National Museum of Natural History’s entomology collection, led by collections manager Floyd Shockley.

Discovering a New Ribbon Worm in the Caribbean

As Natsumi Hookabe snorkeled around Panama’s Bocas del Toro archipelago, she encountered an unusual ribbon worm: large and dark colored, with numerous pale spots. This was her first field experience outside of Japan, and she wondered if this worm was a rare species or just one that she had never seen before.

Hookabe was inspired to study ribbon worms when introduced to them in a university course. Then, after her trip to Bocas del Toro, she found out about a Training in Tropical Taxonomy workshop offered by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in none other than Bocas del Toro, Panama. The rare nemertean that Natsumi found while snorkeling turned out to be a new species, and the first of its kind living in the Caribbean. She named it Euborlasia maycoli, after STRI staff scientist Maycol Madrid, for all his help throughout the Panama workshop, including facilitating her transfer of the specimens she found to her home lab in Japan, which made her discovery possible.

Eighteen Pelican Spider Species Discovered in Madagascar

In 1854, a curious-looking spider was found preserved in 50-million-year-old amber. With an elongated neck-like structure and long mouthparts that protruded from the “head” like an angled beak, the arachnid bore a striking resemblance to a tiny pelican. A few decades later, when living pelican spiders were discovered in Madagascar, arachnologists learned that their behavior is as unusual as their appearance, but because these spiders live in remote parts of the world, they remained largely unstudied.

Fast forward 160 years, when curator of arachnids and myriapods at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, Hannah Wood, began examining and analyzing hundreds of pelican spiders both in the field in Madagascar and in museum collections. She sorted the spiders she studied into 26 different species—18 of which had never before been described.

The spiders Wood personally collected, including holotypes (the exemplar specimens) for several of the new species, have joined the U.S. National Entomological Collection at the Smithsonian, one of the largest insect collections in the world, where they will be preserved and accessible for further research by scientists across the globe.

One Thousand Beetle Species Found along the Chesapeake Bay

More than 25,000 beetle species call North America home and provide services to countless organisms, including each other. As decomposers, beetles aid in the breakdown of forest matter, and they recycle nutrient-rich material back into the ecosystem. As predators, they reduce populations of problem insects, like aphids and caterpillars. By studying beetles at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC), which occupies 2,650 acres along the Chesapeake Bay in Maryland, we can better understand their populations, their roles in ecosystems, and the overall health of the environments they inhabit.

Since 2018, husband and wife entomologists-turned-volunteers Charlie and Sue Staines have devoted most of their time to collecting, identifying, and recording beetles on SERC’s campus. In July 2024, the pair identified their 1,000th beetle species at SERC—Nipponoserica peregrina. A member of the scarab beetle family, this beetle species originated in Japan and primarily lives on plants.

The work of the Staines’ has inspired new research at SERC. Charlie will be working on a new ground-beetle project at BiodiversiTREE, SERC’s massive forest restoration experiment, and a beetle identification guide that will help other researchers and volunteers locate and identify beetles on the SERC campus. Learn about participatory science programs at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, where you can contribute to important ecological research just like Charlie and Sue.