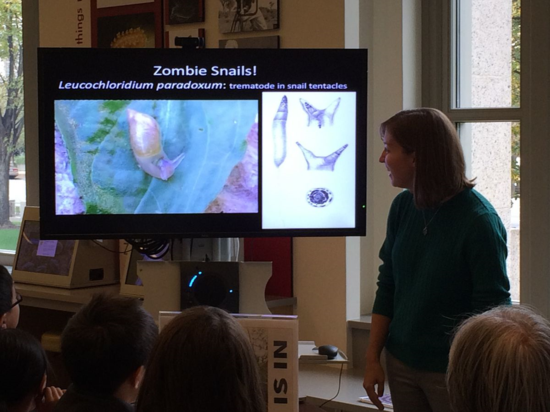

Crazy eyes and mind control—the power of parasites

Have you ever had a pet that seemed just a little bit crazy or odd? Can you be sure that it was in control of its own mind and not something else? The power of parasites often goes unnoticed by most people, but not by invertebrate research zoologist Anna Phillips from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History.

Managing the large collection of earthworms, flatworms and leeches at the museum, Phillips’ research focuses on the relationships between parasites and their sometimes multiple animal hosts. To ensure that they are eaten or picked up by their desired host some crafty parasites use some very disturbing techniques.

Birds beware of the crazy-eyed snail

While snails that have colorful pulsating eye stalks may seem quite appetizing for a bird, they are really something they should avoid, Phillips explains.

leucochloridium-paradoxum-21.mp4

[Video has no audio. Watch snail with colorful pulsating eye stalks.]

Phillips: Snails can get infected with the parasite when they eat bird droppings filled with the parasite’s eggs. This parasite is a type of trematode—a parasitic flatworm that infects mollusks and vertebrates. Inside the snail, the parasite grows and then tunnels into the eye stalks of the animal. Here it pumps embryos into fat, throbbing brood sacs it builds in the snail’s eyestalks, turning the appendages into bright green-banded, pulsating beacons that look like caterpillars.

While these colorful pulsating eye stalks may be attractive to birds, they still need to be able to find the snail to eat it. The parasite has evolved to help move its host out of the darkness, by influencing the snail’s tiny brain to reduce its natural aversion to daylight.

Once a hungry bird finds and eats the infected snail, the parasite finds itself in an optimal host for reproduction. Even if the snail manages to survive, it may be infected with more parasites, meaning that another trematode can emerge in its other eye stalk, beginning the process all over again!

Rats who chase cats

Most rats that smell cat pee would run in the opposite direction. Not those infected with the parasite Toxoplasma gondii. They don’t flee from danger as Phillips explains.

Phillips: Toxoplasma gondii is a single-celled parasite that can infect most warm-blooded animals, including humans, causing a disease called toxoplasmosis. To reproduce sexually, however, this parasite needs to be inside a cat.

One way for the parasite to reach its feline host is to infect rodents. When the parasite infects the rodent’s brain, it removes the rat’s innate fear of cats. So instead of running away when they smell a cat, these rats are undisturbed by the risk of being eaten. This lack of fear increases the chance that the rodent will become dinner for a feline predator, completing the parasite’s life cycle.

No Bones, a blog from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, featuring the fascinating world of invertebrates, inspired this article.