Ancient ink: Iceman Otzi has the world's oldest tattoos

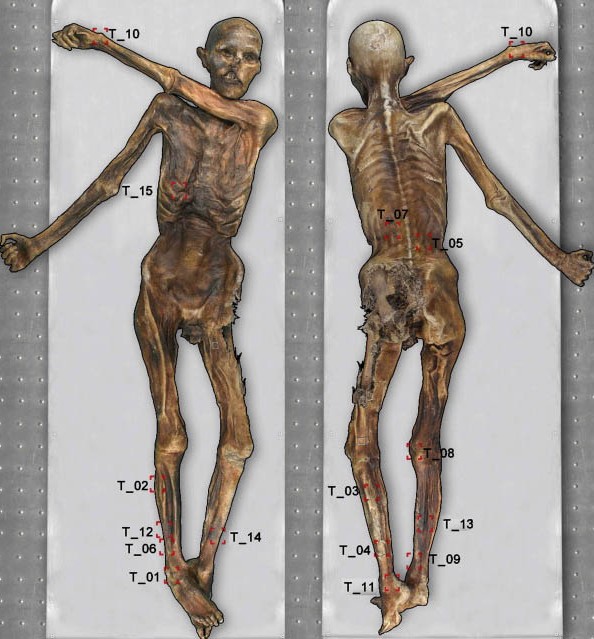

This graphic shows the general location of each of the 61 tattoos on the Iceman’s body. (Photograph © South Tyrol Museum of Archeology/EURAC/Samadelli/Staschitz.)

The debate about the world’s oldest tattoos is over—they belong to Ötzi, the European Tyrolean Iceman who died and was buried beneath an Alpine glacier along the Austrian–Italian border around 3250 B.C. Ötzi had 61 tattoos across his body, including his left wrist, lower legs, lower back and torso.

Previously, tattoo scholars were divided: Many believed that a mummy from the Chinchorro culture of South America had the oldest tattoo—a pencil-thin mustache. Recovered from El Morro, Chile, the mummy was believed to be about 35–40 years old at the time of his death around 4000 B.C.

In their paper published last month in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, four researchers, including Lars Krutak, research associate in the Department of Anthropology at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, concluded that the Chinchorro mummy is not as old as previously thought.

“I was surprised by the findings because in previous publications I brought attention to the tattooed Chinchorro mummy and its early date,” Krutak says. “To me this mummy was like an underdog versus the all-too-popular Iceman that everyone was writing and talking about. But after reviewing the facts, we were compelled to publish the article as soon as possible to set the record straight and stem the tide of future work compounding the error.”

Determining the Age of Tattoos

The art of tattooing is ancient, but when it began is unknown. Written records date the art of tattooing back to fifth-century B.C. in Greece—and maybe centuries earlier in China. Beyond that, evidence of tattooing is found in art, from tattoo tools and on preserved human skin; the latter is the best evidence and only direct archaeological proof.

Archaeologists use radiocarbon dating to date samples, and it was the key to determining if Ötzi or the Chinchorro mummy had the oldest tattoos. (This technique measures the amount of carbon-14 in a dead organism, compares it to the carbon-14 levels in the atmosphere today and gives an estimate of when the organism died.)

Ötzi has been studied for more than two decades. His clothes and tools have been extensively radiocarbon dated, and much is known about his health, environment, death and his tattoos—which may be therapeutic; they are grouped in places where Ötzi suffered from joint and spinal degeneration.

In contrast, little was known about the Chinchorro mummy, so the researchers set out to determine his identity and age and examine his tattoos.

Lost in Transcription

During their work, the researchers found an apparent misreading of the Chinchorro mummy’s radiocarbon dating.

When a sample of his lung tissue was radiocarbon dated in the 1980s, the date was given as 3830 ± 100 B.P. (Before Present, a time scale used in radiocarbon dating.) However, the paper’s authors surmise there was an error, and the radiocarbon date was recorded as 3830 ± 100 B.C. This error was repeated in subsequent studies, pushing the Chinchorro mummy’s age back about 4,000 years earlier than his actual radiocarbon date.

This finding settled the controversy: Ötzi is older than the Chinchorro mummy by at least 500 years.

Although Ötzi is the oldest tattooed human, the paper’s authors conclude this will likely change: Ötzi’s tattoos are indicative of social and/or therapeutic practices that predate him, and future archaeological finds and new techniques should someday lead to even older evidence of tattooed mummies.

“Apart from the historical implications of our paper, we shouldn’t forget the cultural roles tattoos have played over millennia,” Krutak says. “Cosmetic tattoos—like those of the Chinchorro mummy—and therapeutic tattoos—like those of the Iceman—have been around for a very long time. This demonstrates to me that the desire to adorn and heal the body with tattoo is a very ancient part of our human past and culture.”

Thousands of ancient mummies exist around the world in museums and other collections that should be investigated further for tattoos, Krutak adds. “I hope this paper stimulates new research. In turn, we may see the antiquity of tattooing being pushed further and further back in time, which is an exciting prospect.”