This section includes products such as perfumes, aftershaves, and powders. The text below provides some historical context and shows how we can use these products to explore aspects of American history. To skip the text and go directly to the objects, CLICK HERE

|

| Ricksecker's Perfumes advertisment for Martha Washington perfume, Warshaw Collection of Business Americana, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution |

Perfumes were one of the first cosmetic products to be carried by American pharmacies. Fragrant essential oils, along with dried herbs, tinctures, extracts, and mineral salts, were part of the pharmacist’s stock from which medicines and cosmetics were prepared. Oils such as lavender, rose, sandalwood, and musk were used in toilet waters, as well as to camouflage the less-agreeable scents of various salves and ointments. These oils were also used as flavoring for other medicinal products.

Deodorants and antiperspirants, which prevent odors, weren’t widely marketed until the early twentieth century. Before then, people who could afford to mask body odors did so with perfumes applied directly to clothing and handkerchiefs. Soap manufacturers also added fragrances to make their toilet soaps more appealing and to scent the skin of the user.

By the 1900s, name brand cosmetics and hair products were steadily making their way onto the shelves of American pharmacies, and many of these powders, pomades, creams, lotions, and shampoos were perfumed. The development of synthetic scents and new scent extraction technologies made perfumes less expensive to produce and purchase. As a result, perfume became less of a luxury item restricted only to wealthy buyers.

|  |  |  |  |

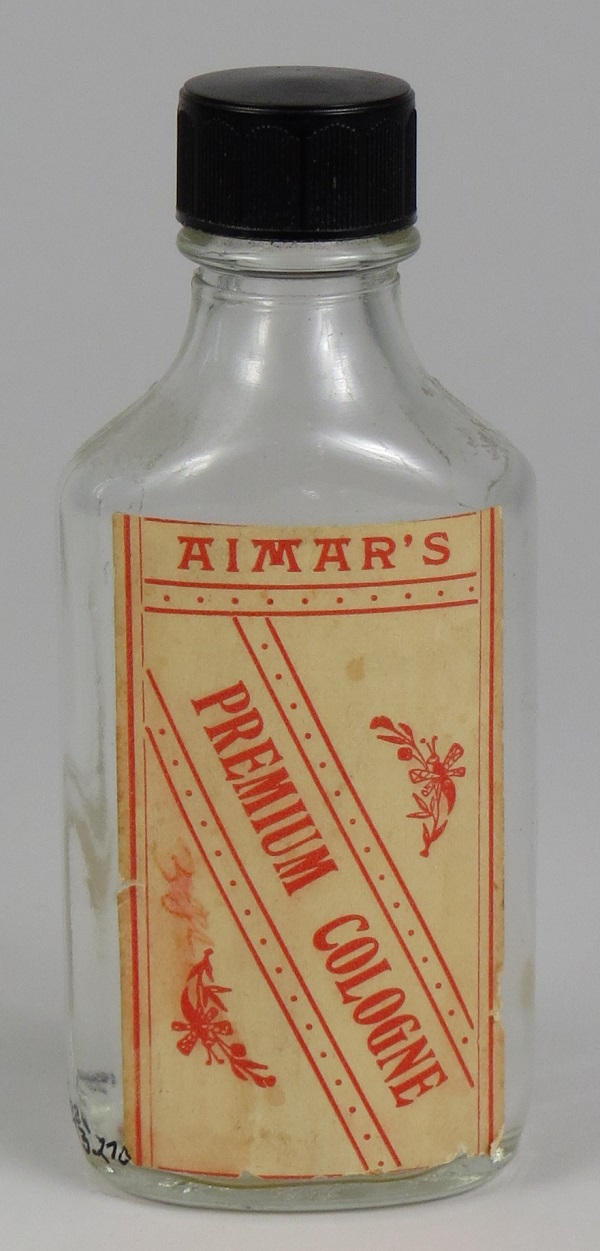

| Azurea Sachet Powder, L.T. Piver, Paris | Lavender Water, Willis H. Lowe, Boston | Jockey Club in apothecary bottle | Maud Miller for the Handkerchief | Aimar's Premium Cologne |

Perfume makers, most of whom were in Paris, considered themselves artisans, and of a higher class than American cosmetics manufacturers and perfumers. American consumers appear to have agreed, for American perfume companies often gave their products French-sounding names.

|  |  |

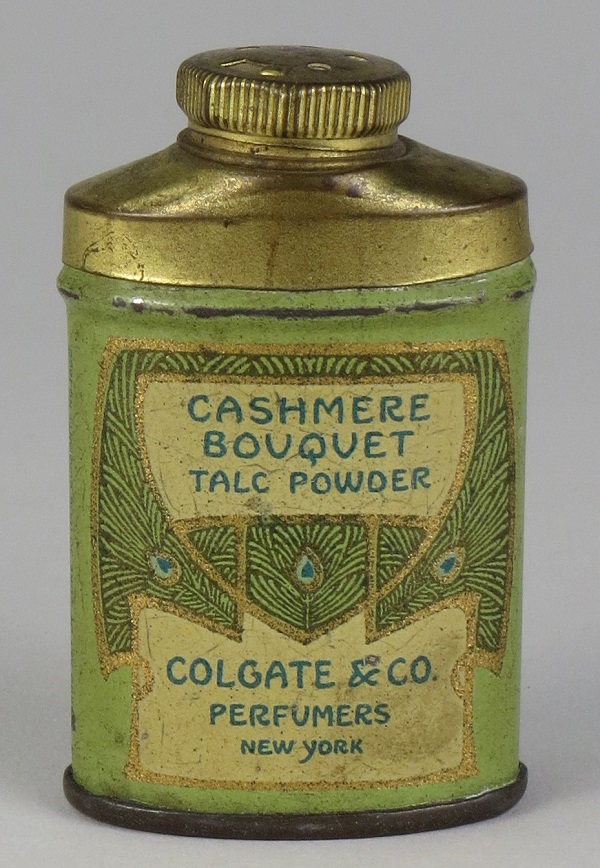

| Cashmere Bouquet Talc Powder | Cashmere Bouquet Perfume | Cashmere Bouquet for the Hair |

Some of the more successful mass-marketed American perfume companies include Solon Palmer, Richard Hudnut, Colgate, who made the longstanding line of Cashmere Bouquet-scented products, and Caswell-Massey, who in 1840 introduced the well-known fragrance Jockey Club. The Museum’s collection contains many examples of fragranced products from these companies.

Historian Geoffrey Jones writes that the success of Frenchman François Coty’s line of fragrances in the American market is emblematic of a major change in the fragrance industry in the 1920s. First, Coty had created a new model for perfume products: he employed jewelry designer René Lalique to create perfume bottles so eye-catching that, as Jones writes, “the bottle came to cost more than the juice within it.” Consumers were willing to pay for small amounts of perfume in exclusive-looking bottles, and Coty had factories that made both the perfumes and the bottles. Second, he was able to successfully market scents across a wider economic spectrum. Finally, Coty invested quickly and heavily in the American market, setting up a separate company to produce perfumes within the United States. Other large, powerful French companies—such as Bourjois, Guerlain, and Caron—made similar moves, opening American offices and sometimes creating perfumes specifically for the American market. These companies were able to dominate the market through powerful brand-identity and advertising campaigns. The perfume industry, previously made up of small perfume houses who sold their scents in generic, mass-produced bottles, evolved into a market composed of large companies that packaged their scents in designer vessels.

|  |  |

| Radio Girl | Guerlain de Paris Shalimar | Charlie |

Before the 1970s, perfumes sold in America were usually either imported from Europe, or manufactured in America to emulate European perfumes. Jones writes that after the launch of the top-selling Revlon scent “Charlie” in 1973, American perfumes became “more sporty and independent than their French equivalents.”

Fragrances marketed to men followed a similar, although slower, trajectory to those marketed to women. Before the early twentieth century, men’s scents were confined to typical barbershop aftershaves, such as Bay Rum and Florida Water. Even then, most men avoided scented aftershaves.

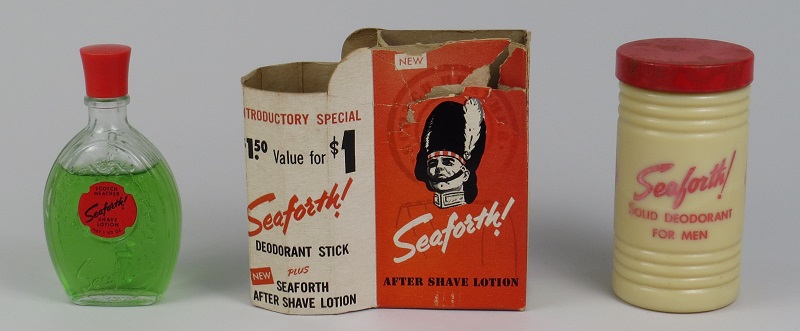

World War II changed the way that men viewed grooming products. Because neat and clean grooming had been a requirement during service, men came home accustomed to using products that kept them clean-shaven, fresh-smelling, and neatly tended. By the early 1950s, now-famous male fragrances such as Aqua-Velva, Seaforth!, Old Spice, and Canoe had become popular.

|

| Seaforth! Aftershave Lotion and Deodorant |

Bibliography ~ see the Bibliography Section for a full list of the references used in the making if this Object Group. However, the Fragrance section relied on the following references:

Jones, Geoffrey. Beauty Imagined: A History of the Global Beauty Industry. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Morris, Edwin T. Fragrance: The Story of Perfume from Cleopatra to Chanel. New York: Scribner, 1984.

Peiss, Kathy Lee. Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture. New York: Metropolitan Books, 1998.