This section includes products such as liniments and salves. The text below provides some historical context and shows how we can use these products to explore aspects of American history, for example, the connections between human and veterinary medicine. To skip the text and go directly to the objects, CLICK HERE

|

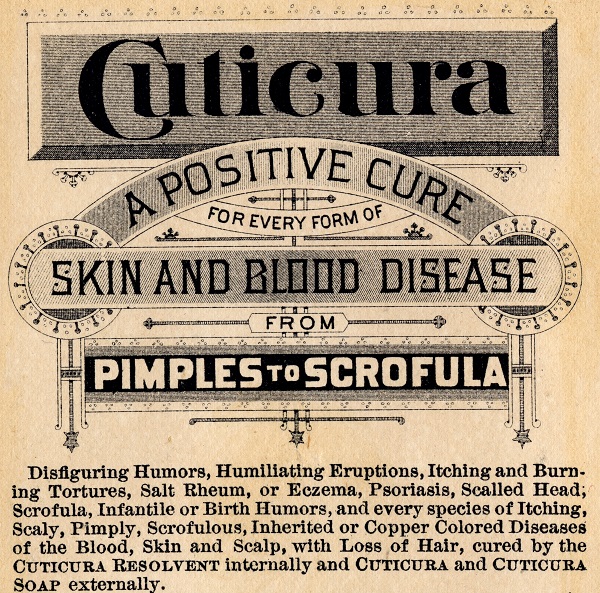

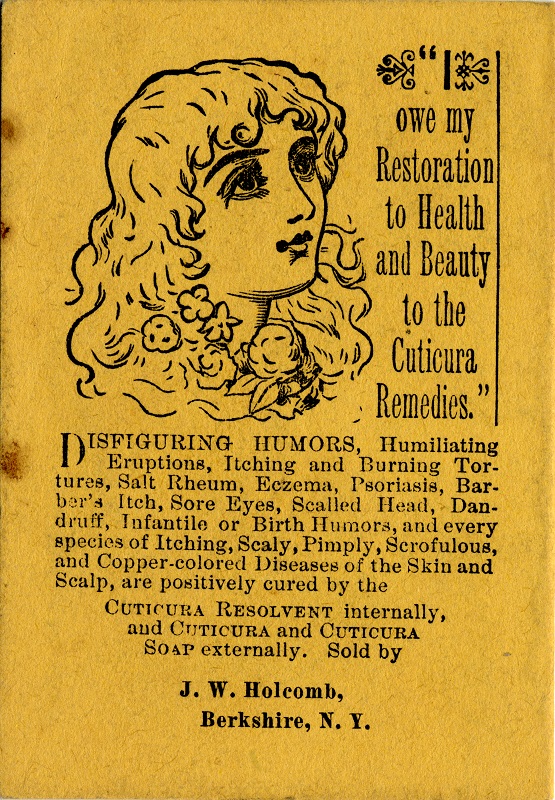

| Cuticura tradecard, Warshaw Collection of Business Americana, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution |

Cure-alls

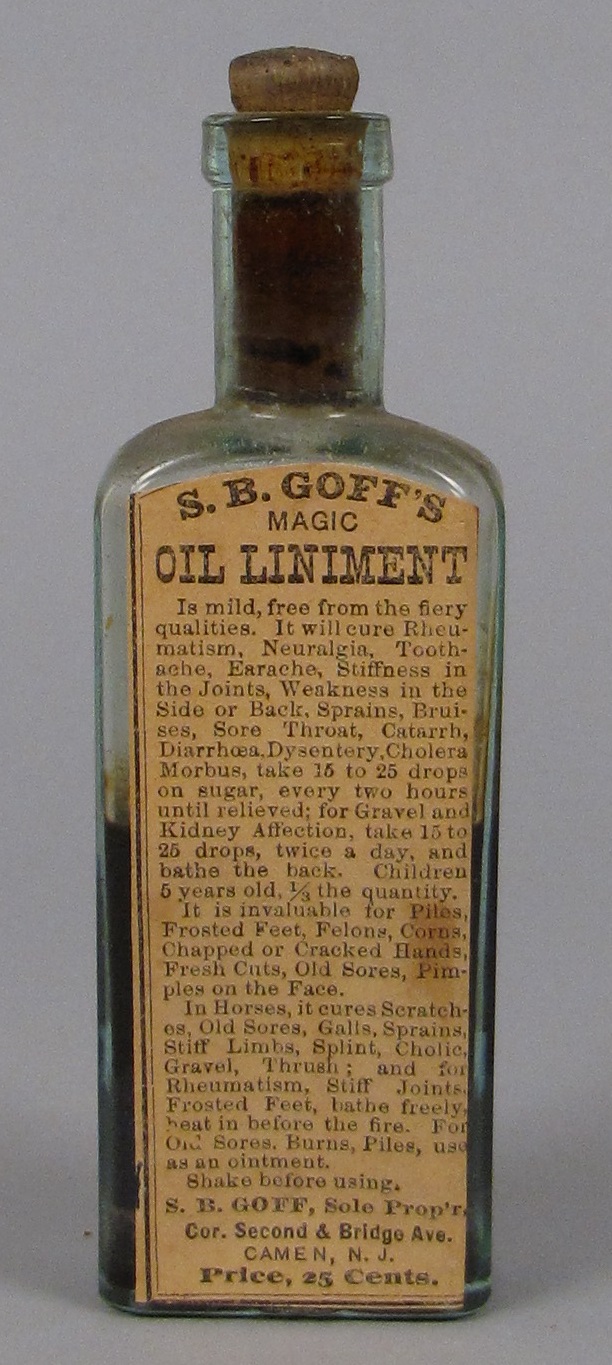

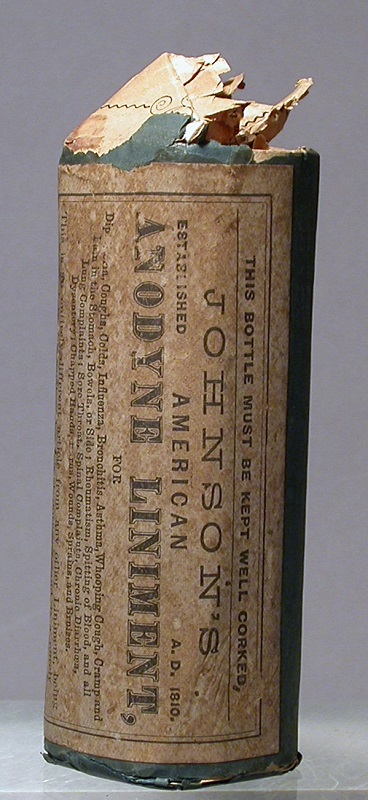

Patent medicines—a common name for proprietary “over-the-counter” products—were hugely popular in America from the mid-nineteenth century until the early twentieth century. During this period, drugs and remedies were largely unregulated, and manufacturers were free to make any health claims they wished about their products. Many patent medicines were “cure-alls,” in that their manufacturers claimed that they cured an enormous number of disparate diseases.

Frequently, these cure-alls also promised to remedy problems with the skin, complexion, hair, eyes, or even the shapeliness of the figure—anything that affected one’s physical beauty or health. Cure-alls began to disappear from the market after legislation was enacted in 1912 that prohibited manufacturers from making false and fraudulent therapeutic claims.

Cure-alls were manufactured both as liquid tonics, which were taken internally, and as salves, balms, or liniments, which were applied topically. Some products were labelled with directions for both internal and external use.

Salves and Ointments, Liniments and Balms

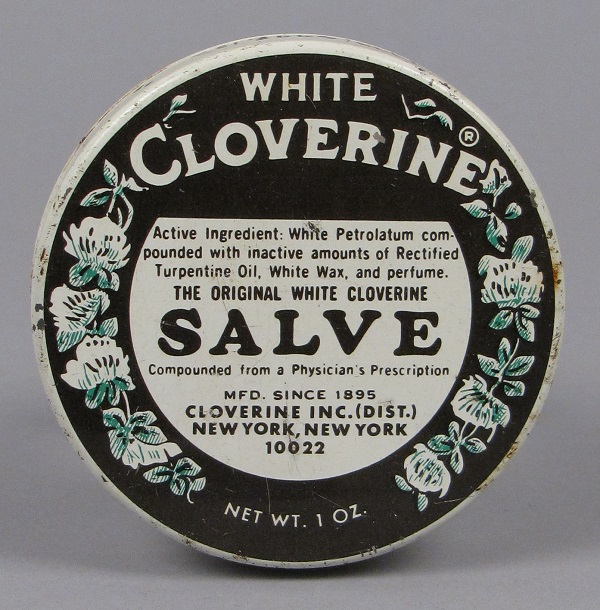

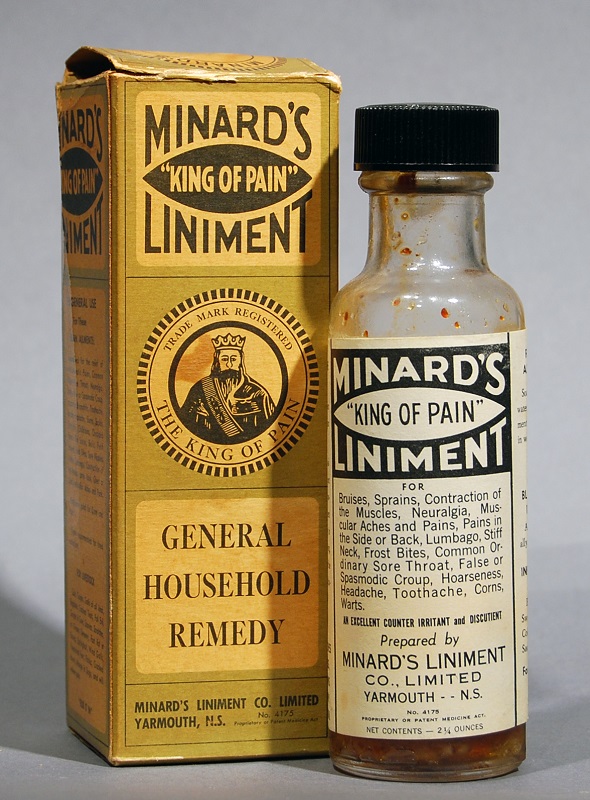

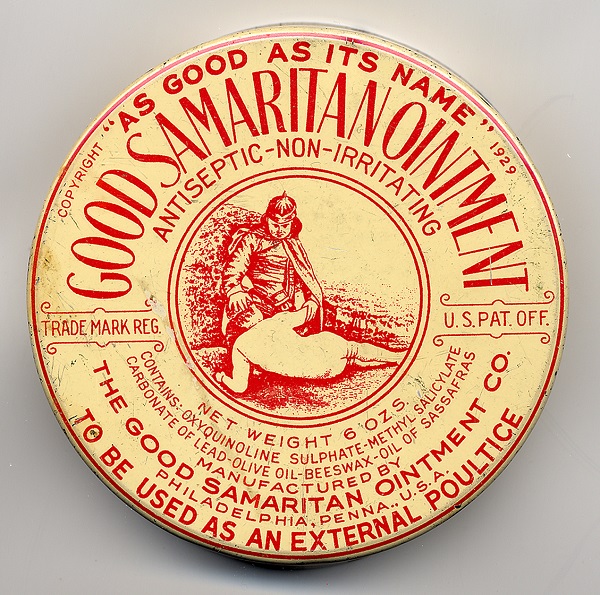

Other salves, liniments, and ointments produced during the same period stopped short of making cure-all claims. These topical preparations were generally used to treat common skin, scalp, and hair problems and can be seen as precursors to the over-the-counter skin care and first-aid ointments in use today. Indeed, some brands of topical preparations produced during the late 1800s, such as Mentholatum, Bag Balm, and White Cloverine, remain available today. Robert Chesebrough patented petroleum jelly under the name Vaseline in 1872, and many of these salves have a base of petrolatum, or petroleum jelly. Salves were packaged in tins, while liniments were generally bottled. Liniments were liquids that often had a high alcohol content, which suspended oils of mint or pepper. The oils acted as a “counterirritant”—they stimulated mild irritation of the skin with the aim of lessening pain or inflammation in other areas of the body.

|  |  |

| White Cloverine Salve | Minard's "King of Pain" Liniment | Good Samaritan Ointment |

Salves and liniments addressed aliments that often brought with them aesthetic concerns. Beauty standards of nineteenth and early twentieth century America placed a high priority on clear skin and full, thick hair. People used these salves and liniments to remedy complexion issues such as pimples and blackheads, as well as scalp conditions, such as ringworm and mange, that cause patchy hair loss. These products served the whole family, and provided both health and beauty help for one price. But they were especially appealing to women who were eager to avoid purchasing specifically cosmetic preparations. At this time, the use of cosmetic preparations was often socially unacceptable.

For Man or Beast

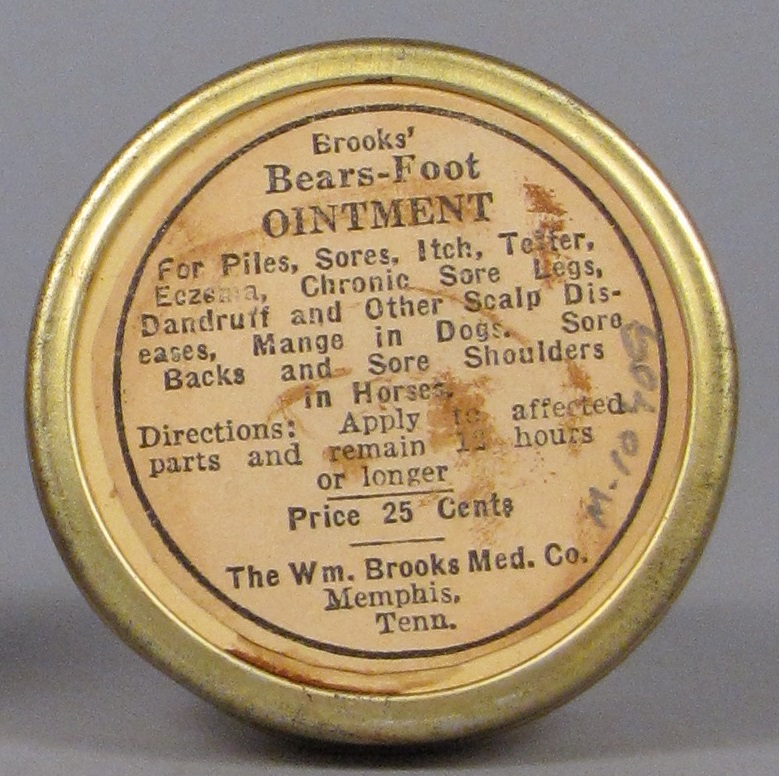

Older salves, ointments, and liniments were sometimes marketed as for “man or beast.” This tactic was especially applicable for products that claimed to cure or soothe minor skin irritations such as cuts, scrapes, burns, insect bites, bruises, chafing, and dry cracked skin that are common to humans and their pets and livestock. Humans and their animals shared some skin ailments because they shared a common environment and were often in physical contact with one another. For example, both the rider and the horse may be tormented by saddle-chafed skin. In addition, fungal infections such as ringworm and parasitic infections such as mange could be easily passed between the family dog and children. Although the packaging for these products included separate directions for application to domestic animals versus humans, the healing action described is basically the same.

|  |  |

| Brooks' Bears-Foot Ointment | Taylor's Oil of Life for Man or Beast | Gentry Brothers Famous Mange Remedy |

Bibliography ~ see the Bibliography Section for a full list of the references used in the making if this Object Group. However, the Cure-alls and Salves section relied on the following references:

Peiss, Kathy Lee. Hope in a Jar: The Making of America’s Beauty Culture. New York: Metropolitan Books, 1998.

Scranton, Philip. Beauty and Business: Commerce, Gender, and Culture in Modern America. New York: Routledge, 2001.