Smithsonian Scientists Discover Basket Architecture of Ancient Algae Shells

A team of researchers from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, University College London and Bremen University recently studied a pristine collection of 92 million-year-old algae fossils (dinoflagellates) from Tanzanian sediments. The assortment of calcareous shells is the most precise geochemical archive from the Cretaceous period to date, and it reveals that simple organisms like algae developed unexpectedly complex structures in early evolution. This new discovery could ultimately help improve the design of everyday materials used in people’s lives. Details from this research are published in the June 18 issue of Nature Communications.

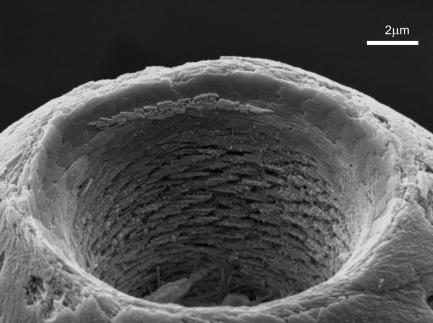

Fossil shells are naturally composed of biomineral structures, and their design is sometimes comparable to man-made architecture. One example are the spicules of a siliceous sponge, which are arranged similarly to the steel pieces of the Eiffel Tower in Paris. The research team found that the structure in the microscopic calcareous shells of certain fossil dinoflagellates closely resembles woven fabrics used in baskets. This design resulted in an optimum balance of strength, flexibility and weight needed to give these organisms protection while preventing them from sinking rapidly in the ocean’s water column.

“Our findings could provide a new, tried and tested natural solution to creating material that is at the same time stable, flexible and light-weight,” said Jens Wendler, a former post-doctoral fellow in the National Museum of Natural History’s Paleobiology Department and lead scientist on the study. The new discovery indicates that the principle of constructing baskets was already known to unicellular organisms millions of years ago, long before humans roamed the planet.

The research team identified the dinoflagellate’s basket-like shell structure thanks to the well-preserved nature of the microfossils. Over time, the minerals in fossils undergo changes during a process called recrystallization. These changes modify the shape of crystals within the fossil shells and often are strong enough to mask the true structure of the fossils themselves. The team’s scientists believe that recrystallization was responsible for hiding the true architecture of dinoflagellates from researchers in most, if not all, previously studied fossil algae collections during the past century.

Algae are abundant organisms that are small in size but play a critical role at the base of the ocean’s food chain, and have been an important part of the marine ecosystem for millions of years. Chalky, fossilized shells are all that remain of certain species of algae, and while seemingly unremarkable to the naked eye, these specimens give scientists important clues about ancient paleo-environments. For example, the chemical composition of a fossil shell depends on the conditions in which it was produced. Researchers who study these fossil specimens can estimate the temperature of the surrounding water in which they formed and hypothesize whether or not polar ice sheets may have been present. These pieces of evidence help inform scientists as they reconstruct the Earth’s climate from millions of years ago.

In the future, scientists from the research team hope to build on their discovery and improve their understanding of how and why complex shell structures developed in ancient algae in the first place. They also plan to use the chemistry of this extraordinary collection of fossil shells to increase our knowledge of the history of the planet’s changing climate.

# # #

SI-273-2013