Smithsonian Scientist Helps Confirm Centuries-old Theory Regarding the Origins of the Sucking Disc of Remoras

Remora fish, with a sucking disc on top of their heads, have been the stuff of legend. They often attach themselves to the hulls of boats and in ancient times were thought to purposely slow the boat down. While that is a misunderstanding, something else not well understood was the origins of the fish’s odd sucking disc. Scientists at the Smithsonian Institution and London’s Natural History Museum, however, have solved that mystery proving that the disc is actually a greatly modified dorsal fin. The research is published in the Journal of Morphology.

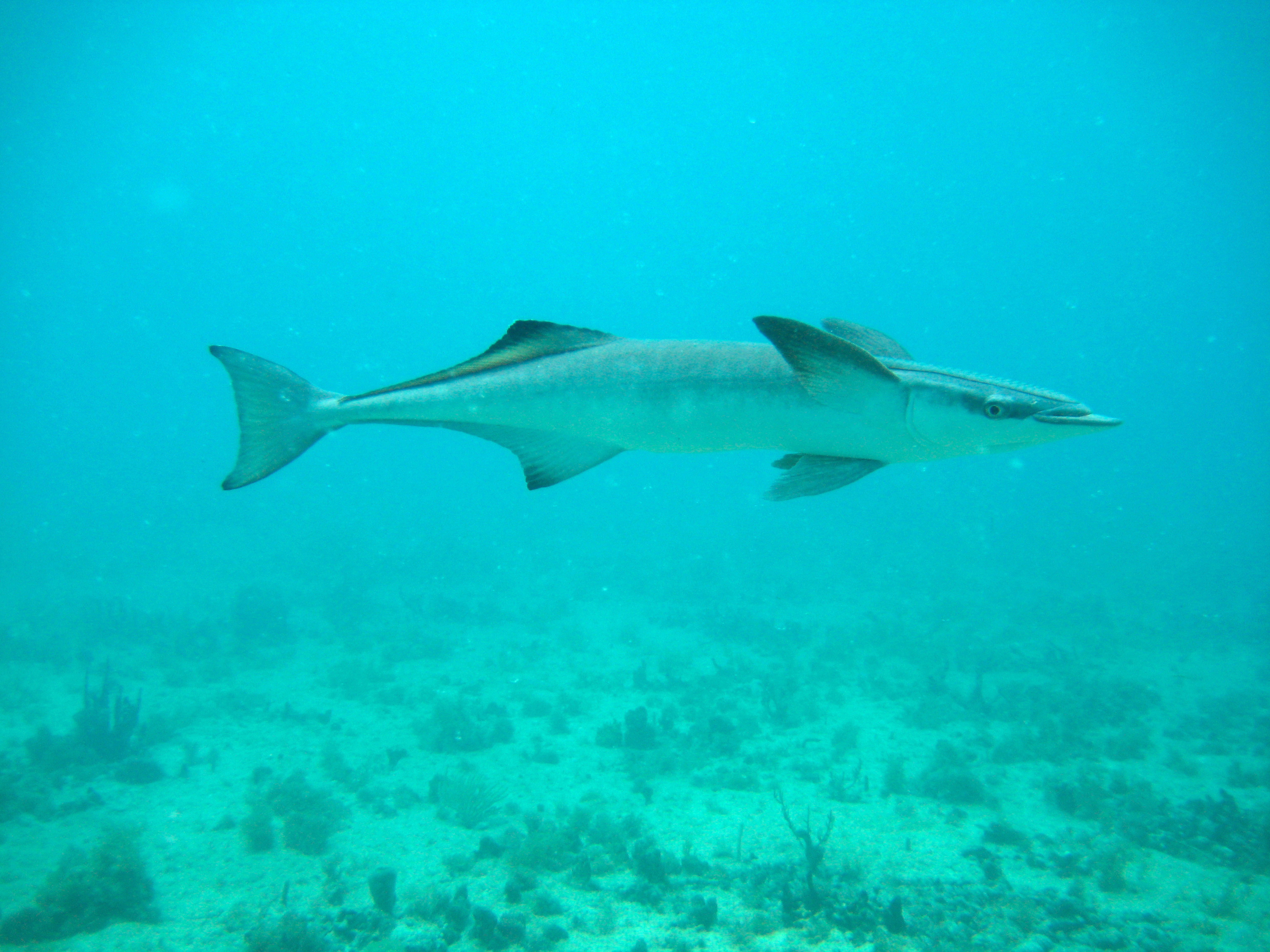

The world’s eight species of remoras range from 1 to 3 feet and are primarily found in tropical open-ocean waters. They use their sucking disc to attach themselves to large marine animals and feed off of scraps of food and parasites from the larger animal.

The idea that the sucker disc is developed from the dorsal fin is not new and dates to the early 1800s. Since then, many scientists have suggested it was derived from the dorsal fin but nobody had studied the development of the remora from its earliest larval stages.

“One reason I think this hasn’t been done before is due to the difficulty in finding early-stage remora larvae” said Dave Johnson, zoologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and co-author of the research. “In our study we closely tracked the development of the sucking disc beginning with tiny remora larvae, through to juvenile and adult remoras. We followed the earliest stages of the disc’s development by matching the first vestiges of elements of the sucking disc with the first vestiges of elements of the dorsal fins of another fish, the white perch (Morone americana), which has the typical dorsal fin of most fishes.”

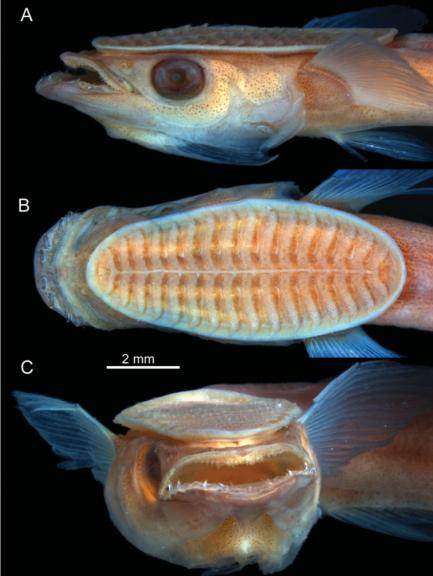

By doing this, the team was able to identify which of three main fin elements—the distal radials, the proximal-middle radials and the fin spines—are radically modified and develop into the different elements of the remora’s unusual disc.

Up to a certain stage in the fish’s development, the dorsal fin can be seen developing in the same way and looking very similar in both fishes. Then, through a series of small changes, the remora’s dorsal fin begins to expand and shift toward the head. By the time the remora has reached about 30-millimeter in length, the dorsal fin has become a fully formed 2-millimeter sucking disc. It still has the components found in the dorsal fin―the tiny fin spines, spine bases and supporting bones―but the spine bases have greatly expanded.

This research thus confirmed that the sucking disc is formed by a massive expansion of the dorsal fin through small changes while the fish is developing. It is not the result of the evolution of a completely new structure.

Before developing their disc, remora larvae have very distinctive hooked teeth protruding from the lower jaw. “Because remora larvae at this stage are relatively rare in plankton collections, I have often wondered, although we don’t have any evidence for it, if maybe remora larvae are not free living in the plankton layer but go into the gill cavities of fishes and use their hooked teeth to hang on until they develop a disc,” said Johnson. “Fodder for future research.”

# # #

SI-229-2013