Smithsonian Presents “For All the World to See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights”

The modern civil rights movement emerged alongside the explosion of TV and popular pictorial magazines. Suddenly Americans were watching scenes of demonstrators—black and white—being beaten and attacked by dogs or by fire hoses turned on at full blast. These images and the movement they documented were powerful enough to change opinions, perceptions and attitudes and became the catalyst for major civil rights legislation. More significantly, positive images in a range of media helped embolden a people and alter their images in the culture at large.

Through photographs, TV and movie clips, magazines, newspapers, posters, books, pamphlets and other media, “For All the World to See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights” examines the role that images played in the fight for racial equality. The exhibition will be on view from June 10 through Nov. 27 in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture Gallery in the National Museum of American History at 14th Street and Constitution Avenue N.W. in Washington.

In September 1955, shortly after 14-year-old Emmett Till was murdered by white supremacists in Mississippi, his grieving mother, Mamie Till Mobley, distributed to newspapers and magazines a gruesome black-and-white photograph of his mutilated corpse. Asked why she did this, Mobley explained that by witnessing, with their own eyes, the brutality of segregation and racism, Americans would be more likely to support the cause of racial justice and equality. “Let the world see what I’ve seen,” was her reply. The publication of the photograph transformed the modern civil rights movement, impelling a new generation of activists to join the cause.

Despite this extraordinary episode, the role of visual media in combating racism is rarely included in the history of the movement. “For All the World to See” looks at images in a range of cultural outlets and formats, tracking the ways they represented race in order to alter beliefs and attitudes.

Images of the civil rights era were ever-present and diverse, including startling footage of southern white aggression and black suffering, photographs of achievers and martyrs in black periodicals and humble snapshots, no less powerful in their ability to edify and motivate. The war against racism and segregation was waged—by civil rights leaders, activists and ordinary people alike—with pictures, forever changing the way political movements fought for visibility and recognition. “For All the World to See,” an exhibition of 230 objects and clips from TV and film, ranging from the late-1940s to the mid-1970s, examines a little-understood aspect of American history and culture.

The exhibition is organized by the Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County in partnership with the National Museum of African American History and Culture. The exhibition was recently named the “Outstanding Exhibition in a University Art Museum 2010” by the Association of Art Museum Curators. The curator of the exhibition, Maurice Berger, is a research professor at CADVC.

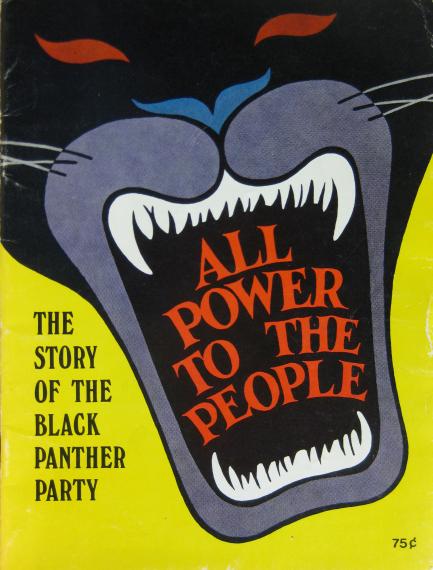

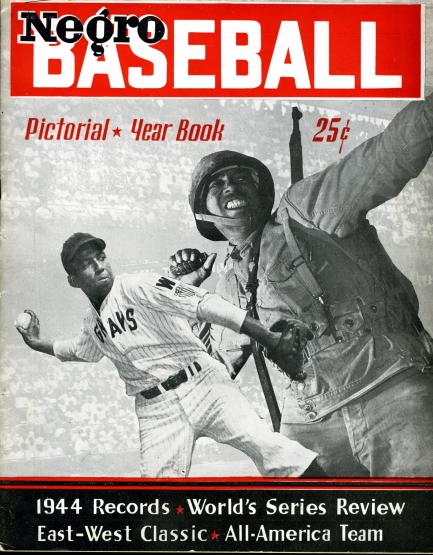

The exhibition is divided into five sections: It Keeps on Rollin’ Along: The Status Quo looks at the world of visual culture into which the modern civil rights movement was born and the power of these images to perpetuate stereotypes, prejudice and complacency. The Culture of Positive Images investigates the role of images in fostering black pride and accomplishment as well as improving the negative view of African Americans in the culture at large. Let the World See What I’ve Seen: Evidence and Persuasion considers the use of pictures to report, document or offer proof—depictions powerful enough to alter public opinion, perceptions or attitudes about race in America. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner: Broadcasting Race examines the role of entertainment TV in supporting black performers and exploring controversial racial issues. In Our Lives We Are Whole: The Images of Everyday Life studies the roles played by the visual artifacts of daily life—from family snapshots to the visual campaign of the Black Panther Party—in emboldening black pride, maintaining the status quo or countering mainstream values and points of view.

Exhibition highlights include materials relating to the Till case, such as a rare pamphlet by the photographer Ernest Withers recounting the murder and its aftermath; historic footage of Jackie Robinson’s first game in the major leagues and other sports memorabilia; an examination of the Negro pictorial magazine, from the widely read (Ebony, Jet and Tan) to the short-lived (Hue, Say and Sepia); photographs documenting the civil rights movement and its leaders by Roy DeCarava, Elliot Erwitt, Benedict Fernandez, Joseph Louw, Francis Miller, Gordon Parks, Robert Sengstack, Moneta Sleet, Carl Van Vechten and Dan Weiner; clips from groundbreaking TV documentaries, most not seen in decades, such as The Weapons of Gordon Parks, Ku Klux Klan: The Invisible Empire and Take This Hammer; and excerpts from nationally broadcast (The Beulah Show, East Side, West Side, All in the Family and The Ed Sullivan Show) and local African American TV programs (Soul, Say Brother and Colored People’s Time).

Funding for the exhibition has come from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Trellis Fund, the National Endowment for the Arts, St. Paul Travelers Corp., the Texas Foundation and the Maryland State Arts Council. Additional support has come from CBS News Archives, Ed Sullivan/SOFA Entertainment, Sellmark Corp. and Sony Pictures Entertainment.

Selected as the 10th exhibition of the NEH on the Road initiative, “For All the World to See” will be adapted for travel to more than 30 cities through 2017. It also has been designated a “We the People” project by NEH. The goal of the “We the People” initiative is to “encourage and strengthen the teaching, study and understanding of American history and culture through the support of projects that explore significant events and themes in our nation’s history and culture and that advance knowledge of the principles that define America.”

“For All the World to See: Visual Culture and the Struggle for Civil Rights” is accompanied by a 224-page, richly illustrated companion book by Berger with a foreword by Thulani Davis and published by Yale University Press. Visit www.foralltheworldtosee.org for a comprehensive online version of the exhibition.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture was established in 2003 by an Act of Congress, making it the 19th Smithsonian Institution museum. It is the only national museum devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, art, history and culture. The Smithsonian Board of Regents, the governing body of the Institution, voted in January 2006 to build the museum on a five-acre site adjacent to the Washington Monument on the National Mall. The building is scheduled to open in 2015. For more information, visit nmaahc.si.edu.

# # #

SI-240-2011