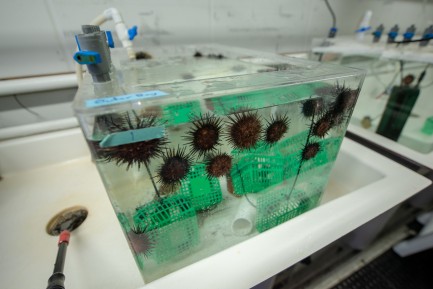

Sea urchins (Echinometra lucunter) in the lab at the Smithsonian’s Bocas del Toro Research Station in Panama. Researchers discovered that low oxygen conditions seemed to effect urchin behavior more than higher temperatures or low pH (ocean acidification).

One-Two Punch: Sea Urchins Stuck Belly-up in Low-Oxygen Hot Water

As oceans warm and become more acidic and oxygen-poor, Smithsonian researchers asked how marine life on a Caribbean coral reef copes with changing conditions.

“During my study, water temperatures on reefs in Bocas del Toro, Panama, reached an alarming high of almost 33 degrees C (or 91 degrees F), temperatures that would make most of us sweat or look for air conditioning—options not available to reef inhabitants,” said Noelle Lucey, post-doctoral fellow at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI).

Lucey and her team showed that when temperatures were at their highest, oxygen levels were lowest, and the water was most acidic. These stressful times for reef animals occurred at night when scientists do not typically make observations.

To test the responses of sea urchins to these alarming conditions, they designed experiments to separate the effects of acidity (pH), oxygen and temperature. Conditions in the ocean change quickly, so the experiments were designed to reflect this, and they only exposed the animals to different sets of conditions for two hours at a time.

The area of the study encompassed an entire bay and nearby, offshore waters. In that area, Hospital Point reef is one of the best places to collect the rock boring sea urchin, Echinometra lucunter.

“The urchins are so common there you don’t even think about putting your foot down,” said STRI Fellow Eileen Haskett, a co-author. “When the surf isn’t too rough, you can see them hiding in every crevice and reef crack, happily pounded by the waves. When the sunlight hits them perfectly, they shimmer with bright purple and red colors.”

Lucey and Haskett collected hundreds of urchins. In the laboratory at STRI’s Bocas del Toro Research Station, they exposed these prickly creatures for two hours to the severe hot, hypoxic and acidic conditions sea urchins may experience on local reefs.

After their exposure to high temperatures, acidity, low oxygen or combinations of the three, the researchers flipped the urchins upside down. When a sea urchin is flipped, it usually immediately rights itself, using its spines and tube feet. In nature, if they do not right themselves quickly, they may get tossed against the rocks by the surf or eaten by reef fish.

The experiment clearly showed that it was much harder for sea urchins to right themselves after being in oxygen-poor water. More acid conditions did not seem to affect the urchins’ behavior. However, sea urchins were also less able to find their footing and flip right-side up after exposures to high temperatures. Most survived and were returned to the reef but the low oxygen and high temperature exposures resulted in some mortality.

The researchers conclude that ocean acidification may not be nearly as important as lack of oxygen (hypoxia), a factor that has not received as much attention in discussions of global climate change. In fact, even though high temperatures, acidity and low oxygen occur at the same time, the team found that together they did not affect the urchin’s performance any more than lack of oxygen alone.

“What really caught my attention was the relationship between extreme low oxygen and high temperatures even out at the offshore sites,” Lucey said. “It shouldn’t be surprising because the relationship between increasing temperatures and decreasing oxygen is well known, but it is somehow eerie to find this in your own data, in your own little part of the world.”

“More and more often, tropical reefs experience severe conditions that, as we have shown, push the limits of marine organisms,” said Rachel Collin, STRI staff scientist and co-author. “A lack of oxygen and high temperatures are bad news for these reef animals. These severe conditions are occurring more frequently and for longer periods of time, upping the stress levels experienced by important reef organisms like sea urchins.”

“Showing how animals react to several forms of stress at the same time helps us understand how marine life is affected by changing conditions, and what conditions to look out for,” Lucey said. “We were surprised to find that such hot, hypoxic and acidic conditions all occur even on a reef that gets plenty of wave action. Our realistic experiments are alarming—showing the levels of oxygen already occasionally found on this reef have such a negative impact on these sea urchins.”

This work was made possible with support and funding from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institution, especially the staff of the Bocas del Toro Research Station, and with support from the local community in Bocas del Toro.

The Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, headquartered in Panama City, Panama, is a unit of the Smithsonian Institution. The institute furthers the understanding of tropical biodiversity and its importance to human welfare, trains students to conduct research in the tropics and promotes conservation by increasing public awareness of the beauty and importance of tropical ecosystems. Promo video.

# # #

Lucey, N., Haskett, E., Collin, R. (2020) Multi-stressor extremes found on a tropical coral reef impair performance. Frontiers in Marine Science. 7:588764. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.588764

SI-344-2020