Museum-inspired manicures: Smithsonian collections spark creative designs by three nail artists

From America's cultural icons to the neighborhood nail salon, nail care and fashion have long been a form of self-expression.

Singer, dancer, and actor Lena Horne exuded elegance with her manicured nails as a key part of her signature look throughout a multi-decade career on stage and screen. Her dresser set—including nail care tools as well as a comb, brush, and mirror—is in the collection of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, a nod to her impeccable stylishness.

In 1993, two nail salons in Washington, D.C. donated examples of their unique nail art designs to Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum. These designs included abstract art, re-creations of pop-culture figures, and seasonal trends.

Over the last 30 years, nail art has only gotten bigger and bolder, increasingly capturing public attention. In 2024, nail art was everywhere, from track and field athlete Sha’Carri Richardsons’ patriotic set at the Paris Olympics, to Cynthia Erivo’s dynamic reflection of her character in the film Wicked at red carpet events around the world.

Behind these notable nails are creative designers who craft high impact art on tiny canvases, pushing the boundaries of wearable art to capture a feeling and communicate a story.

But what if nail artists drew inspiration from the Smithsonian?

Three talented nail artists—Ameya Okamoto, Santana Walker, and Celeste Hampton—visited the Smithsonian's collections and exhibitions to answer this question. Each artist found connections to her own story and community, which sparked handcrafted designs with a touch of Smithsonian inspiration.

The Art of Care and Belonging

“I moved around a lot as a kid, so I had to find belonging not through geographic location, but more within myself and through other people.” - Ameya Okamoto

Nail artist and entrepreneur Ameya Okamoto was inspired by the story of Asian Americans through the lens of work and community.

Ameya examined objects and learned stories related to the history of labor and industry in the U.S. in the 19th and 20th centuries at the National Museum of American History’s Many Voices, One Nation exhibition. She met with curator of Asian Pacific American history Sam Vong for a behind-the-scenes look at more objects from Asian American history, such as tools used in Vietnamese refugee and nail tech Catherine Hann’s studio and fashion worn by Japanese immigrants to Hawaii in the early 1900s.

She also visited the Smithsonian American Art Museum. As she walked through the contemporary art galleries, she was transfixed by Nam June Paik’s Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, prompting her to reflect on how historic ideas of home and place can be represented in art.

Ameya’s focus on home and belonging was even more evident when visiting Sightlines: Chinatown and Beyond, an exhibition presented by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center and on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Her final nail art set reflects a concept design of the Friendship Archway in Washington, D.C.’s nearby Chinatown, which is featured in Sightlines. In Ameya’s version, she scales down the landmark arch to replicate the unique columns and colors, even including her own name spelled out in Chinese and Japanese on each thumbnail.

Ameya’s experience allowed her to contend with her own identity and create art that reflects the complicated relationship between identity and home. “[Identity] is so much bigger than place,” Ameya observed. “I’m constantly searching for belonging everywhere.”

Decolonizing your Manicure

“My grandmother said to me… ‘It’s your inherent right to practice the art of your people, and what you’re doing [with your work] is art revitalization.’” - Santana Walker (Squamish Nation)

Indigenous entrepreneur and nail tech Santana Walker, a member of the Squamish Nation in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada delved into the intersection of contemporary art and tradition during her visit to the Smithsonian.

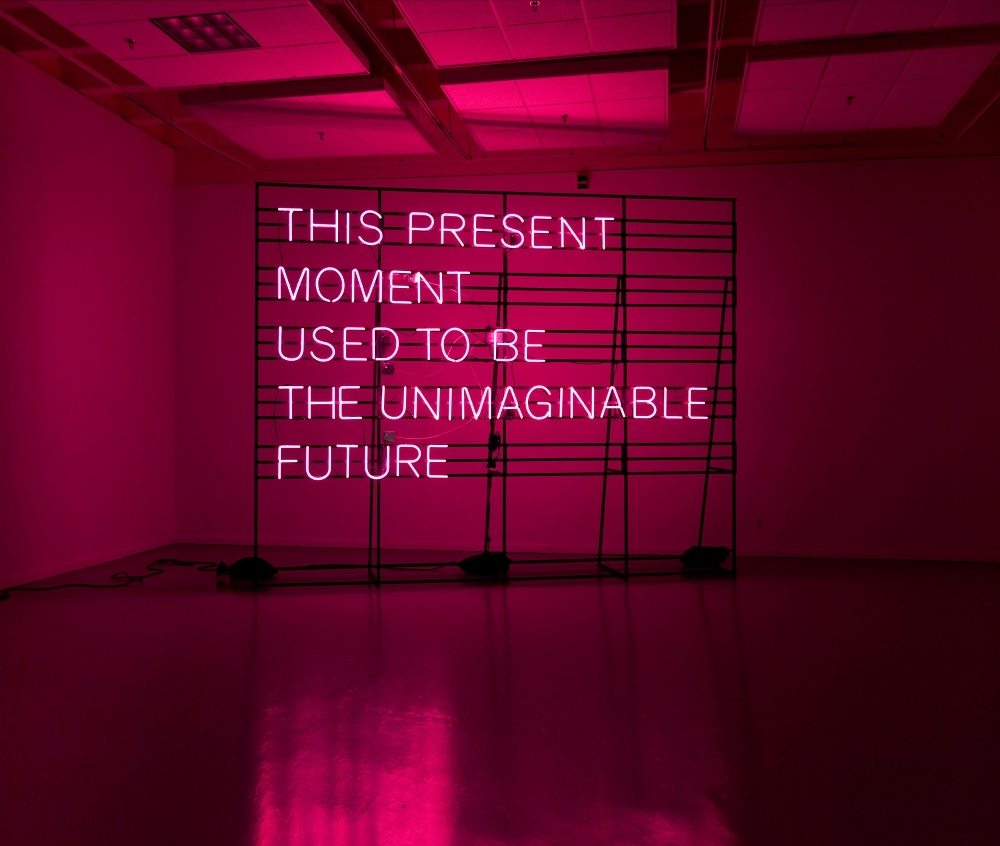

At the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s Renwick Gallery she saw artworks dedicated to contemporary crafts that push the boundary of what we interpret handmade to mean today. Reflecting on the room-sized work This Present Moment by Alicia Eggert, Santana said, "When I read something like [the message in This Present Moment], I believe that. What was once the unimaginable future is now our future.” But it was Preston Singletary’s Safe Journey that most captivated the nail artist. Santana grew up seeing the traditional bentwood boxes of Northwest Native communities that are passed down through families and sometimes used as burial boxes—but none like this. Created as a memorial for the artist’s father, Safe Journey is made of glass, not wood, and glows in a transcendent blue that resonated with Santana. She pointed out Singletary’s use of formline, a style using a continuous line to delineate figures in Pacific Northwest Indigenous art, which is the same art form she practices in her nail designs.

At the National Museum of the American Indian’s Cultural Resources Center in Suitland, Maryland, Santana got a behind-the-scenes look at items created by members of her own community, both historic and modern. Wearing looks designed by Native fashion designers of the Pacific Northwest coast, Santana was also thrilled to see clothing from other Indigenous fashion designers in the museum’s collection.

Reflecting on her own experience as an Indigenous artist, Santana remarked, “throughout the history of Indigenous people, our culture, and our practices [...] they tried to wipe it out essentially. With art revitalization, we are now putting it on everything.” She continued, “We’re Indigenous people, and we want everyone to know.”

After a full day of visiting the Smithsonian and learning, Santana was still thinking about Singletary's Safe Journey. When she returned to her studio, she experimented with different methods to translate the translucent and formline elements of the spirit box into Smithsonian-inspired nails. And who knows, you may see more. Santana shared, “This visit has been incredible, I have so many ideas already [...] I might be doing Smithsonian nails for the foreseeable future.”

Reclaiming Space and Time

“…[Black women] need to continue to demand our positions in this world, reclaiming our time not just as women but through our other voices: our nails, hair, clothing, styles, and unapologetic personalities.” – Celeste Hampton

Artist and entrepreneur Celeste Hampton celebrates the intersection of creativity and wellness.

At the National Museum of African American History and Culture, Celeste explored the intersection of labor and leisure in exhibitions such as Reclaiming My Time featuring Rachelle Baker’s illustration Kitten Meal, and Mickalene Thomas’s You’re Gonna Give Me The Love I Need. Reflecting on how the artworks represented a sense of being at peace, Celeste noted, “Kitten Meal represented Black women as we are together.” In addition, Celeste saw moments of her own history in the gold bamboo earrings and hot comb within the "Style” section in the Cultural Expressions gallery. “It is a beautiful blessing to see me.” Celeste continued, “I grew up watching my mom do hair, so to be able to see the women in the hair salon and then being able to turn around and see the hot comb that was used back then, [...] I never thought that those things meant as much as they did. My history is in here.”

At the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Celeste wandered the floors of the Luce Foundation Center and walked under Glenn Kaino’s sculpture, Bridge, suspended from the ceiling. But it was when she entered the Galleries for Modern and Contemporary Art that Celeste was in awe. “When I saw the Portrait of Mnonja [by Mickalene Thomas], it stopped me in my tracks.” Reflecting on the painting, “[Thomas] took time to think about the depth and the beautiful complexity of the Black woman and put it in a painting.”

Celeste was so inspired by Portrait of Mnonja, that she was still thinking about it back at her studio. Focusing on the elements of the painting that spoke most to her, Celeste interprets the bold colors, patterns, rhinestones, and textures, including replacing Thomas’s depictions of tassels with actual tassels, in her own design. To Celeste, this painting, and her interpretation of it reinforced her belief that “[as Black women], our lights are meant to shine, our skin is meant to be seen, and our voices carry historical volume because they were meant to be heard.”

This project received support from the Digital Initiatives Pool Funds, administered by the Smithsonian Office of Digital Transformation.