The Smithsonian’s top seven scientific achievements of 2024

Celebrate the many 2024 Smithsonian science achievements with a beautiful image of the crab nebula. Nebulas are giant clouds of dust and gas, often forming after a massive star explodes (what astronomers call a supernova). The Crab Nebula is the result of a bright supernova explosion witnessed by Chinese and other astronomers in 1054 CE. Image: X-rays from Chandra (blue-violet and white) and IXPE (purple); optical from Hubble (red, green, and blue).

From naming a new horned dinosaur species to creating a roadmap to protect biodiversity on the moon, Smithsonian scientists were busy in 2024.

A New Species of Dinosaur is Named

Image: ©Andrey Atuchin for the Museum of Evolution in Maribo, Denmark.

Joe Sertich, a paleontologist from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama and Colorado State University, co-authored a study that named a new species of dinosaur. Lokiceratops rangiformis, meaning “Loki’s horned face that looks like a caribou,” was a plant-eating dinosaur with two huge blade-like horns on the back of its frill. The dinosaur, excavated from the badlands of Northern Montana just a few miles from the US-Canada border, has the largest frill ever found on the back of a horned dinosaur.

A Bird Species Returns to the Wild

Six siheks (also called Guam kingfishers) are officially living in the wild in the tropical forests of Palmyra Atoll. The 2024 release marks the first time since the 1980s that these beautiful birds have lived in the wild.

The release is the result of years of work by the Sihek Recovery Program, a global collaborative of conservationists dedicated to reestablishing the sihek in the wild with the goal of returning to its homeland in Guam. The Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute coordinated egg selection and transfer and managed the care of the birds along staff from the Zoological Society of London.

A total of nine young siheks—four females and five males—were hand-reared for several months at the Sedgwick County Zoo. The sihek then traveled from Wichita, Kansas, to temporary aviaries on The Nature Conservancy’s preserve and research station on Cooper Island, the largest of the small islands in Palmyra Atoll. Specialists cared for the palm-sized birds, ensuring that the sihek safely settled into their aviaries, received daily feedings, and acclimatized to their new homes.

A Wetlands Atlas that Can Help Fight Climate Change

Coastal wetlands are carbon-storing juggernauts—in terms of weight, a football field-sized area of a wetland contains the equivalent of nearly eight tractor-trailers’ worth of carbon. This ability to store carbon makes them critical players in mitigating climate change. Due to how much carbon they store, many nations rely on wetlands to help them slash or offset greenhouse gas emissions. However, since no two wetlands are identical, it is difficult to know how much carbon any given wetland is storing.

To help governments better understand their carbon storage, scientists at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center created a map of more than 15,000 soil samples from six continents—and the map is still growing. The Coastal Carbon Atlas is already helping states, such as Maryland, calculate how much carbon they can save by conserving wetlands, or lose by destroying them.

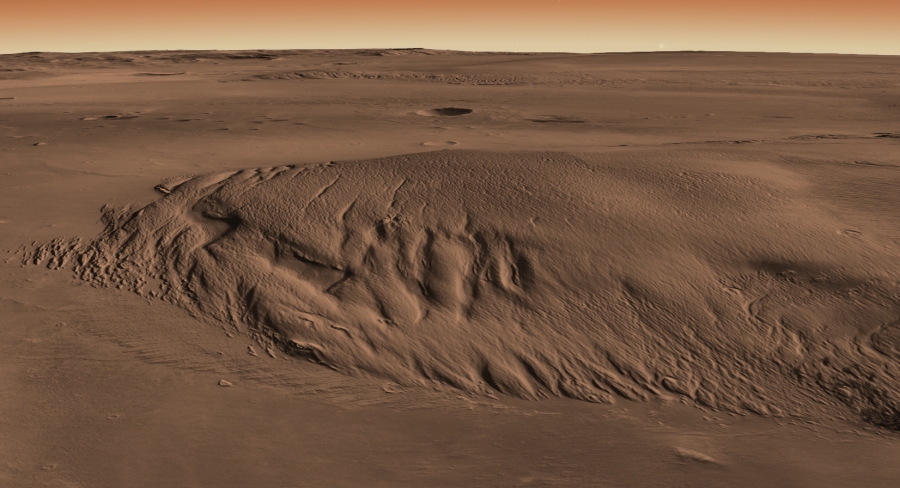

A Geological Formation on Mars Gets Less Mysterious

Credit: Caltech/JPL Global CTX Mosaic of Mars/Smithsonian Institution.

The Medusae Fossae Formation (MFF) is a collection of hills and long mounds that cover large areas of Mars near its equator. The geological deposits within the MFF remain one of red planet’s enduring mysteries. Once thought to be composed of a mix of windblown rock, sediments, and volcanic ash, emeritus senior scientist Thomas Watters from the National Air and Space Museum Center for Earth and Planetary Studies discovered that the MFF also features a two-mile-thick layer of ice just below its surface. The ice, if melted, would yield enough water to cover the surface of Mars to a depth of about 5 to 10 feet. The study reveals a previously unknown, major reservoir of water in the equatorial zone of Mars and provides new clues about the ancient climate of the planet.

An Update to When Bioluminescence Evolved

Scientists from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History found that bioluminescence first evolved in animals at least 540 million years ago in a group of marine invertebrates called octocorals. This date pushes back the previous record for the luminous trait’s emergence in animals by nearly 300 million years. The discovery could one day help scientists decode why the ability for living things to produce light evolved in the first place.

Chandra Celebrates a Birthday

Credit: NASA/SAO/CXC.

To celebrate the 25th anniversary of its launch, NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory released 25 never-before-seen views of a wide range of cosmic objects. The Chandra X-ray Observatory—the most sophisticated X-ray telescope built to date—is a collaboration between NASA and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. It was launched into orbit on the space shuttle Columbia on July 23, 1999.

X-rays, which are invisible to the naked eye, reveal extremely hot objects and very energetic physical processes. The X-ray images captured by Chandra illuminate dynamic regions in space, such as the debris from exploded stars and material swirling around black holes. Today, astronomers continue to use Chandra X-ray data to learn more about everything from exploded stars to exoplanets to the mysteries of black holes and dark matter.

A Biodiversity Vault on the Moon

Researchers from the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute, National Museum of Natural History, National Air and Space Museum, and other institutions proposed a plan to safeguard Earth’s imperiled biodiversity by cryogenically preserving biological material on the moon. The moon’s permanently shadowed craters are cold enough for cryogenic preservation without the need for electricity or liquid nitrogen.

The authors outlined a roadmap to create a lunar biorepository, including ideas for governance, the types of biological material to be stored, and a plan for experiments to understand and address challenges such as radiation and microgravity. The study also demonstrated the successful cryopreservation of skin samples from a fish currently stored at the National Museum of Natural History.