Meet a Scientist A closer look at the people behind the research

Meet a Scientist A closer look at the people behind the research

On the hunt for parasites in animal poop

River otters are unequivocally cute. But their eating habits are not so adorable. Most animals—humans included—separate the place where they defecate from the place where they eat. But river otters eat, mate, and play where they go to the bathroom.

Katrina Lohan knows this intimately. She is often called the “otter lady” at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) because of her research on river otter poop. She found otters regularly defecate (as well as play, mate, eat, and dance) in particular locations along the Rhode River on SERC property, where she is a coastal ecologist.

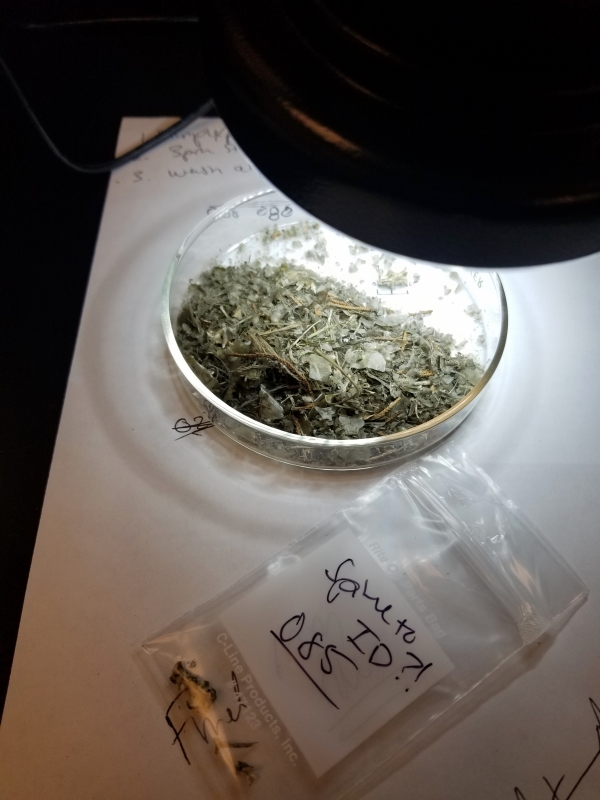

River otters are a top predator in the area, so their poop is full of DNA from worms, fish, and other organisms, including parasites. For Lohan, river otters’ diets and bathroom habits make the carnivores the perfect subject for her research on the spread of parasites in the environment.

Lohan’s interest in ecology originated with her love of water. As a child, Lohan didn’t live near water, but she visited the ocean whenever she could. “I wasn’t the kid playing with bugs in my backyard. Instead, I wanted to go to the beach,” she explained.

After graduate school, Lohan wanted to study marine biology in Hawaii, but she was referred to the Smithsonian’s National Zoo. There, Robert Fleisher was using DNA to study parasites in migratory birds. “I didn’t know anything about birds or parasites, but I figured DNA is DNA and all things have it, so it doesn’t matter what animal I study,” Lohan said. She left the lab with a love of parasites.

“Trying to study something inside something else that's really small and hard to see…that really interested me,” Lohan said. “Parasites play a big role in nature. They kill things we want to eat. They destroy ecosystems. They infect animals that, in turn, can infect us. They also have an out sized role in how animals interact. Parasites compose as much as half of the living species on this planet, which means that when we talk about biodiversity, they play a huge role.” Lohan’s passion for parasites is unrelenting, even though studying parasites means spending a higher-than-average amount of time handling animal poop, because that’s where parasites are often found. She also works with oysters, crabs, and other coastal animals.

Sometimes, parasites infect animals by being eaten (by living in prey that animals eat), and then the parasite’s DNA often ends up in the animals’ digestive tract and is expelled with the rest of its waste. As a result, poop is a goldmine when studying parasites in nature. River otter poop is no exception, and Lohan’s research can show what parasites are likely present in humans in the same region to help keep our food and water safe.

When Lohan is not digging through poop and analyzing the DNA inside, she mentors students whenever she can, and serves on panels related to gender equity in science. “I once heard the phrase ‘we lift as we climb’ and I loved it.” She is proud to lift students up as she climbs her own ladder at the Smithsonian.

“I can’t help but use my privilege to help others who don’t have that privilege and who like science but don’t have an opportunity to experience it. It’s amazing to see how far some people have come.” She does not take her affiliation with the Smithsonian for granted. She wants to use her position to help others advance in their careers. “The Smithsonian name is really trusted. To have someone use that on their CV and to write letters of recommendation for them, I’ve seen that really open doors.”

Whether through birds, river otters, or any other animal, if Lohan can pass on a love of parasites to the next generation of female scientists, she considers that a win.

Meet a Scientist tells the stories of the people behind the research, the discoveries they make, and their inspiration. We explore their passions, celebrate their contributions, and look more closely at how questions become solutions that can inform environmental policy, spur technological innovation, and promote community and collaboration across the globe.